What if you could do three cases per hour of practice?

And what if these three cases were actual quality practice?

“You can’t be serious, Bruno. No one can pull off that many cases per hour. Doing cases is time-consuming, you know. You gotta find the people, give feedback and all that…”

Yeah, I know. But suppose for a minute you could. What would change?

While everyone’s struggling to practice 10-20 cases per month, you’d be doing 50 AND having your social life back.

Some people are okay doing a few cases here and there. They’re fairly content with the 2-3 cases they’re pulling off every week.

Maybe they have several months to prepare, or maybe they are so confident in their abilities they don’t fear being rejected. Perhaps they’d be happy working in another field, so they don’t care too much getting an offer from a top consulting firm.

I wasn’t one of those people back then.

Even though I practiced a lot, I always felt I needed more. “If the interview were today, I wouldn’t be able to handle every possible M&A case”, my obsessed mind would think.

And there I went, searching for other candidates who could do M&A cases with me. A week later, the obsession would be Public Sector (probably triggered by a public sector case that just caught me off-guard). Then, in no time, I was trying to find a way to better read charts (the newest feedback I got from some random internet guy who had just talked to a BCG manager about it).

It seemed like an endless cycle of fear, self-doubt and obsession with a certain case type or question. There was no end to it, as there were always new case situations to consider.

Doing more cases just felt like the most natural way to break this cycle…

I felt like I could get there if I just did more cases. But would I have the time for that?

My dreams of fixing all my problems by doing 10 or 20 more cases would turn sour as soon as I did just two or three of them. Only then would I remember how tough it was to even schedule one of those. I had to be lucky for the other candidate to make it to our meeting on time. Then, lucky again that the random guy from the internet was at my level.

But even that wasn’t enough. I had to hope they’d have a case that covered whatever skill I was trying to improve at the time. If I was desperate to learn to get insights from charts and the case didn’t have a chart, I’d just wasted myself an hour or two of my time.

And then, after doing a whole case, I had to be lucky enough that the other person was both kind and tough enough to give me useful feedback. What’s the point of reading the damn chart and not knowing what specifically to improve?

Sometimes it would take me three or four cases to get good practice on whatever I needed.

With so much luck involved, no wonder people feel you need to be lucky to get an offer from McKinsey, BCG and Bain.

All I wanted was to find a way to improve on the things I knew I had to get better to perform well on interview day. To feel in control of my preparation, instead of wasting my time.

What I needed was to do more cases without sacrificing quality. Or, better yet, to do more cases and having BETTER quality – all of them on point, with great, specific feedback on my performance.

A couple weeks before my final rounds I stumbled upon a solution: targetted practice drills.

It was a bit late for me to benefit from this discovery. But I got to teach others. This is a practice Julio and I have taught coaching clients over and over again and that they greatly benefited from. Targetted drills are one of the pillars of our method.

So what are these “drills” and how should you use them?

A drill is a basic exercise that isolates one specific aspect or type of question in a case interview. It is quite intuitive in other fields. If you’re a basketball player having trouble with shooting the ball what you’ll intuitively do is to separate some time just to practice shooting. You do that in parallel with playing whole matches. Both are going to be part of your practice. In a case interview context, if you’re having trouble structuring cases, why not practice structuring in isolation using some of the time you’d spend doing full cases with other people?

For some reason still mysterious to me, this is not what most candidates (including past me) intuitively do!

I’ve talked to a candidate once who said he was having a lot of trouble doing the initial structure of revenue growth cases. When I asked him how many cases of this type had he tried to structure in the past his answer was revealing: “not so many, it’s actually quite hard to find people who know a case like that to give to me in the first place”. This was a guy who was practicing 2-3 hours per day and it never occurred to him that he could practice the initial structure of these types of cases by himself.

I’ve seen people getting feedback to improve their estimations from consulting firms who were “just doing more cases” instead of practicing estimations. I’ve seen people with trouble reading and interpreting charts counting on luck to get cases with charts. No wonder these people feel their practice isn’t focused enough and that they’re not progressing!

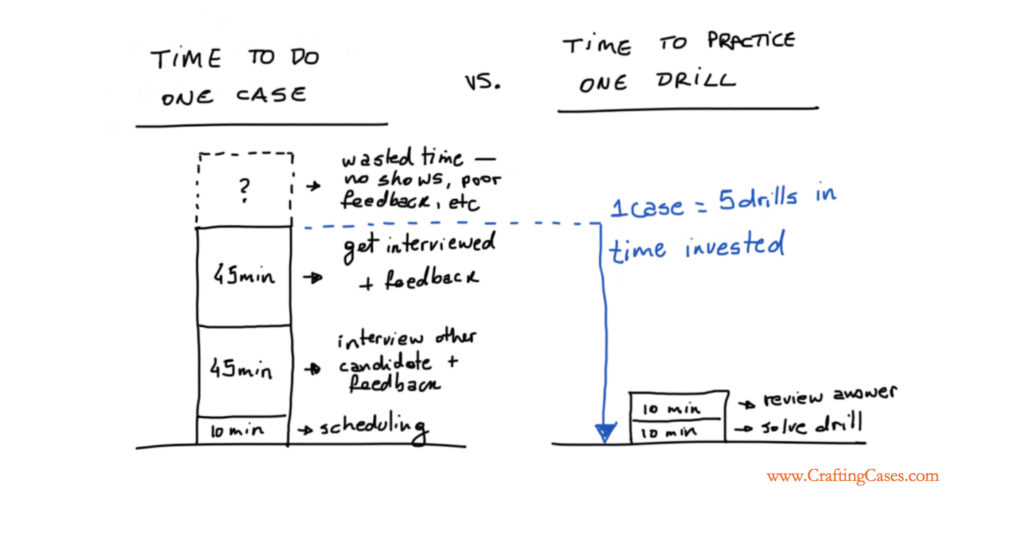

Doing drills of the specific aspect you’re trying to improve on is the one lever you can pull that will improve your preparation effectiveness the most. Because the drill will tackle exactly your area of improvement, the value you get from doing one of those is often equal and sometimes higher than the value you get from doing one full case with another person. Since you can do one drill in 10-20 minutes, you’ll be able to get the value of doing at least three cases per hour. If you’ve got one hour per day, that’s about 100 cases per month. Impressive, to say the least.

Before you object, you should never fully stop doing full cases. Why? For the same reason a guy that practices shooting the basketball all day long and nothing else will never be a good basketball player. Drills are a great addition to every candidate’s preparation schedule. Here are a few ways our ex-clients used this practice to overcome their weaknesses:

- We once had a client who was great at structuring and had an incredible business intuition. However, he missed the quantitative analyses of 8 out of 10 cases and would never get an offer due to this. We prescribed him a routine of 2-3 quantitative analyses per day (about 40-60 minutes of work). In just two weeks he was getting 9 out 10 analyses right AND catching his own mistakes quickly on the ones that went wrong. He got a dream offer at BCG and credits much of his success to this targetted practice.

- A candidate who had to balance work and school while preparing for his case interviews at Bain had to rely almost solely on drills due to a lack of time to find other case partners. About 90% of his prep time was spent doing drills for Frameworks, Brainstormings, Estimations and Quantitative Analyses. It was his second time applying, so he had the advantage of knowing the case interview format well, but the drills gave him enough skill and confidence to finally get the offer.

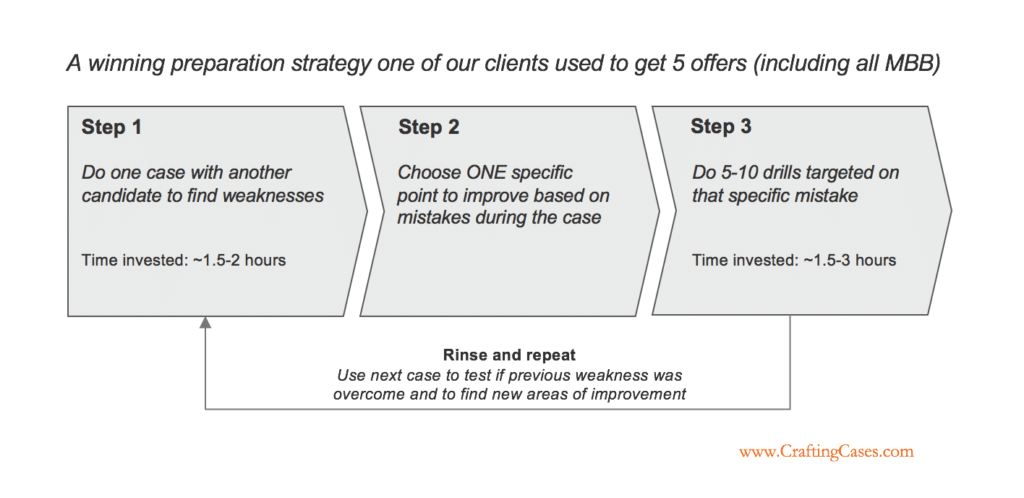

- A client of ours used a smart combination of drills and practice cases to get 5 different offers, including McKinsey, Bain and BCG. She would do a case with us or another candidate, choose one specific point where she made a mistake (e.g.: having a MECE structure to answer the Brainstorming question) and do 5-10 drills focusing on that specific thing. Then she would get back to do a full case with another person to see (i) if she improved on that aspect in a realistic situation and (ii) to find another mistake. Later in the process she doubled down on drills, for she was better than most candidates in just about everything and was learning more from this type of practice than doing cases with other people.

By including drills in your practice regimen you can greatly improve how focused and effective it is. I know of no other habit that improves the learning curve for case interviews as much as this one.

But there’s one question left to address.

What specifically should I do to include drills in my practice?

It’s so much easier to just keep doing cases and not bother with this new thing, right?

I know it’s hard to start something new. Even if it’s a simple thing, our heads tend to get bogged down into the small details that come up ahead. And suddenly we’re back to old habits again. Just doing more and more cases and getting frustrated by the lack of progression. Feeling guilty and anxious that we’re not doing enough or not improving as we thought we would.

But I really want you to succeed, and I firmly believe that doing drills is the simple shift that will get you on that steep learning curve again.

So here are three steps to start doing your drills right now:

Step 1: Choose ONE Building Block to practice and have ONE or TWO specific goals for that.

If you’ve known us for a while you know we’ve designed and strongly advocate the Building Blocks approach to learning cases: instead of case types, focus on the question types your interviewer will ask you. These questions are the building blocks of any case interview, no matter what genre.

So go ahead and choose ONE Building Block to practice. You may want to practice Estimations, or decision-making Frameworks, or Chart Interpretation. Even if you want to improve on several of them over the mid to long-term, chose just one to improve now. Then go a step further: pick one or two specific goals for that Building Block and focus your work on those.

For example, say you want to improve your decision-making Frameworks. One goal could be to be able to create a good enough structure for strange or out-of-the-box cases (such as public sector ones). Another type of goal could be to always find at least three insightful ideas that are super-specific for that case and show great business sense. Or it could be to always have a Toothbrush Test Score above 60%. Or to improve one specific aspect of your communication, such as to be more concise.

What specific goal you pick doesn’t matter as much as simply picking one. By having one you’ll be able to systematically track your progress.

Step 2: Find a good source of drills

Now that you know what types of drills you need, look for a good source of them. You can use a specific tool for that or simply a casebook.

You’re looking for two things: number of questions of the type you need and answer quality.

A casebook that is perfect for Framework drills (because it has different case types and good examples of Framework answers) isn’t necessarily the best for Estimation drills. A casebook with detailed explanations of the Quantitative Analyses may lack any Charts for interpretation.

We believe the quality of drills is important, which is why Julio and I develop our own drills for our clients. Looking for a good source of drills is a good investment of your time. Let me know in the comments if you’re having trouble with this and I’ll do my best to help you out.

An alternative to finding a good source of drills is to come up with your own. For estimation questions, for example, any market or business number that you try to estimate will be useful to improve your skills. You can create your own lists of drills and go through them. You won’t have answer examples, but the third step partially solves that problem.

Step 3: Have a step-by-step process and a performance checklist for the type of drill you’re practicing

It’s alright to simply practice with no system in place, but that’s clumsy and risky. It’s not the best you can do. The best you can do is to work systematically and take no risks.

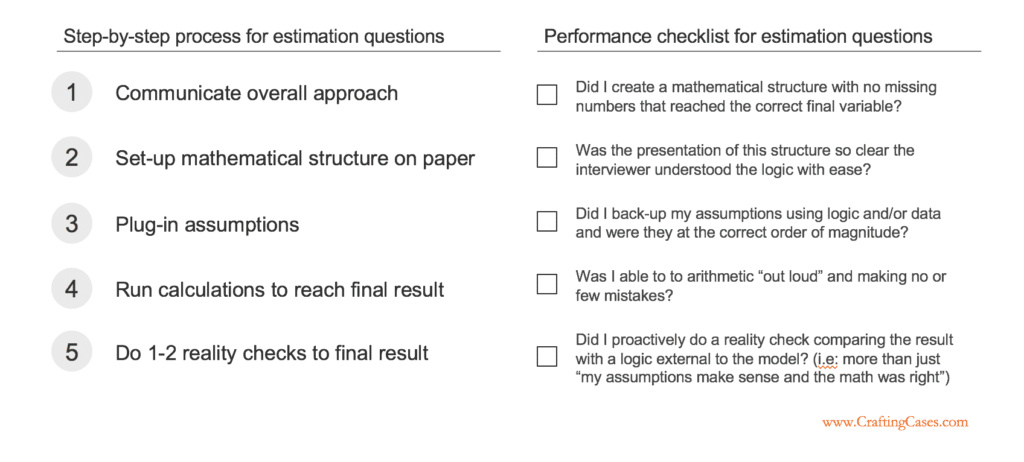

I’ve once worked with a client who messed up the math even though she was an engineer from a top school. She had no idea what was going on. The solution? I gave her a step-by-step process to solve the analytical questions and a simple performance checklist for those. She quickly discovered that her mistakes always had the same root cause even though she didn’t see it beforehand.

Before mindlessly practicing, think about what you want to achieve (the performance checklist) and set a step-by-step process to do it. Here’s an example: a step-by-step process to solve estimation questions and a simple checklist that tells you how well you did on the question and where have you messed up:

That’s it, now, time to do some drills!

If you’re like most candidates who have been practicing for more than a month, you’re frustrated with how much your improvement has slowed down. You wish not only that you could do more cases, but that each case you did were more useful. You wish you weren’t wasting your time with cases that you’re proficient in already or with mock-interviewers who don’t know what they’re talking about or won’t spend their energy giving you useful feedback.

I’ve offered you a way out.

My goal was to leave you with no excuses, tell me in the comments if I did my job right.

Is this a perfect solution? No, it’s not. In the perfect world you have access to a whole team of patient MBB consultants that will guide you through every nook and cranny of the case interview process. They will rub your back and prepare you lattes to make you feel comfortable and give you nice yet helpful feedback. Then you’ll go out to relax in a sunny park while a soft breeze gently waves your hair as beautiful unicorns walk by you and a rainbow forms in the horizon.

And because this perfect world exists in our minds, many who will read this article will choose not to go through the hassle of doing these “weird drill things”.

Others, though, won’t want to count on luck to get quality practice. And I hope that’s you. It doesn’t feel good to go to such a high stakes interview hoping the situations you’re not prepared for won’t happen. It’s much better to be prepared for whatever happens. I know this, I’ve been to interviews well and ill-prepared. It’s just so much better to actually know what you’re doing when the tough questions come.

And what’s something you can do right now to get closer to that level of preparation? Well, to follow the 3-step process I just described above and do a few drills. Here are the next steps if you missed them:

- Choose a type of drill to do – frameworks, estimations, brainstormings, it doesn’t matter. Whatever you feel like improving.

- Open a few casebooks and choose the one that has the types of questions you’re looking for and quality, detailed answers for those. No need to be perfect.

- Sketch a step-by-step process to answer the question type you feel comfortable with and jot down a few bullet points of things you would like to achieve in each step of the answer. Again, perfectionism will only get you stuck. Doing the work will help you improve an gain awareness of other things to improve.

Then do three drills 🙂

And do a couple more tomorrow.

Now, would you please do me a favor? I’m really curious why people do not use drills in their preparation as much as they should.

So, tell me why you haven’t used them so far (if that’s the case). Or, if you prefer hypotheticals, share why do you think most candidates focus the larger share of their time doing cases with other candidates vs. doing targeted drills that address their specific weaknesses.

Share your views in the comments and I’ll make sure I answer each one of them!