Our first client ever didn’t get his job offer at Bain.

Back then, Julio and I were just out of MBB and investigating how to start another business (a coffee brand!). But we were also flirting with case interview preparation. We loved to teach and people were asking for our help. Then this guy from London decided he wanted to pay us to help him out. He had two weeks left to prepare to his only shot: Bain & Company. We rolled up our sleeves and took the job.

He did well enough on his first rounds and got a shot with the partners. His feedback was to improve structuring, just like most of you guys.

Then things went south.

The partner threw a tough case at him, and he was able to create a good structure to start the case with. They went through discussing a couple of issues until the interviewer asked him a qualitative question. Our client started jotting down a structure to answer his question until hearing the partner say, with friendliness: “hey man, no need to write, just say what’s off the top of your head”. He started listing ideas. That was his fatal mistake.

He later got a call thanking him for his time. The feedback? “You weren’t structured enough.” When he probed deeper, he found his lack of structure was mainly throughout the case. One example given was that qualitative question the partner asked him to answer off the top of his head. He was devastated.

Our first client happened to neglect to structure what we call a “Brainstorming question”. We have never let any other client repeat the same fatal mistake again.

Now, I’ve told this story to quite a few people before and their reaction is always the same: “that partner was a jerk! He misled him into thinking he could be unstructured”. True enough, but here’s exactly where the mistake is. As a management consultant you can never be unstructured, and because the very first principle of structuring is to be MECE (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive; or no overlaps and no gaps), you always need to have a MECE structure to answer any question. Even if you’ve never thought about the problem before. Even if your interviewer doesn’t give you time to think on paper.

Good management consultants make it a habit to think and communicate using MECE structures. Not only do they do it while doing everything work-related, I would constantly see them doing it when talking politics over lunch, planning an event, even when talking to their romantic partners. There was office lore at McKinsey that a guy had proposed his now wife using a MECE structure and telling her the three reasons why he wanted to marry her. (I know, incredible).

It is easy for us to think MECE, because we do it every single day of our lives, and so does everyone around us.

Candidates, however, struggle a lot to use the MECE principle in their structures. This is generally why they often have to make the hard choice between using a random framework from a book (that will get them rejected when they get a case isn’t fit for it) or creating a structure that is too poor to pass (because it isn’t MECE).

To get in, you need to think and communicate like a true consultant. So if you want an offer from a top consulting firm, you need to learn to use the MECE principle in all your structures and most of your communications. That’s something every management consultant does every day.

But why do consulting firms and their consultants care so much about MECEness?

Having a MECE structure to solve a problem is much like having a well-charted map to navigate a territory.

A good map allows you to plan your journey so you’re sure you can reach the endpoint even before you start the trip. Starting a consulting project (or a case interview) without a well-done structure is reckless. It is like promising someone you’ll get somewhere by a certain time and having no idea if it’s even possible. You can try and may even succeed, but you’re counting purely on luck. Consulting clients are not willing to bet their own careers on luck.

MECEness is not only one of many desired qualities in a good structure, it is the most important.

Having a structure that isn’t “Mutually Exclusive” is like navigating with an untrustworthy map that was drawn out of scale. You might reach your destination but it will be a confusing trip. If you get lost along the way it’s going to be difficult to get back on track. Estimating when you’ll get to the endpoint will be an exercise bound to get everyone involved anxious. Almost as critical, it is going to be tough to explain to people how you got there in the end. Consulting is all about having clarity on next steps: to have the project under control and to have everyone on the project and client team on the same page. You need the “ME” part to do that.

Using a structure that is not “Collectively Exhaustive” is also dangerous. Your map is missing parts, and you don’t even know which ones are missing. Nor how important they are. When Columbus set sail to modern day India he found the Americas instead, something huge that was not on his map. While that led to a great discovery, this is not how you want to approach your management consulting projects or interviews. You want to have things under your control, and being “Collectively Exhaustive” is how you do that.

Having a MECE structure enables clear thinking and to have the problem under your control. But it doesn’t end there. It also enables efficiency. Say two people need to go from Point A to Point B. One has a well-charted, complete map and the other one just a rough sketch of part of the way. Who would you bet is going to get to Point B first? All things equal, the first person has a huge advantage.

There are three main reasons you should always be MECE.

Let’s take a step back and bring the analogies back to a case interview or consulting project situation. The three reason why consulting firms value MECEness in their consultant’s thinking are: clarity of thinking and communication, elimination of blind spots and work efficiency.

The first reason, clarity of thinking and communication, is all about understanding what needs to get done so the project can finish.

You’re at Point A and you know which steps need to be done to get to Point B.

Imagine you’re in a project or solving a case interview where Point A is “your client is in a weak competitive position, losing revenues and profits” and Point B is “they want to know whether they should buy their competitor or not”. Having a MECE structure allows you to know the 3 or 4 or 5 steps or analyses or pieces of work that need to be done before you can recommend yes or no to your client. Having this clarity of thinking enables your project’s partner, client or interviewer to clearly understand from the outset how are you going to answer their question. What things you’re going to investigate and what things you’re not going to investigate to give them the answer. They can then sleep peacefully knowing their problems will be solved in time. A well-slept client is a happy client, and a happy client makes a happy partner.

The second reason to be MECE is the elimination of blind spots. I call this “bulletproofing your problem-solving approach”.

Exhaustiveness covers for these. Anxious partners and consultants want to have full control of the project from the outset. They want to know what they know and what they don’t know. They want to have a Plan B in case things don’t go as planned. In order to have those, you need a full understanding of all the things that are relevant to solve the problem at hand. No Americas appearing on your way to India. Something on your blind spot isn’t seen until it happens to cause an accident. Unforeseen accidents cause clients not to sleep peacefully, and you know what happens then.

Finally, the third reason, work efficiency.

Consulting firms are obsessed with efficiency not because they’re thrifty, but because some of the best projects happen to have huge time constraints: competitive threats and reactions, corporate crises, sensitive M&A movements. Also, they’re expensive. Clients want it fast and working long hours only goes so far. Working smarter is a better, healthier approach. The best consultants can reach a good recommendation 5-10X faster than average ones, and being great at structuring is a big part of the reason why.

So you want to be MECE when breaking down problems because that plays a huge role if your goal is to get an offer from a top management consulting firm. And the role is that big because MECEness ensures projects that are clearly communicated, efficient and under control.

But how does that play out in practice?

Let’s go through a couple of examples of MECE and non-MECE structures in case interview scenarios to see what happens when you aren’t MECE vs. when you are.

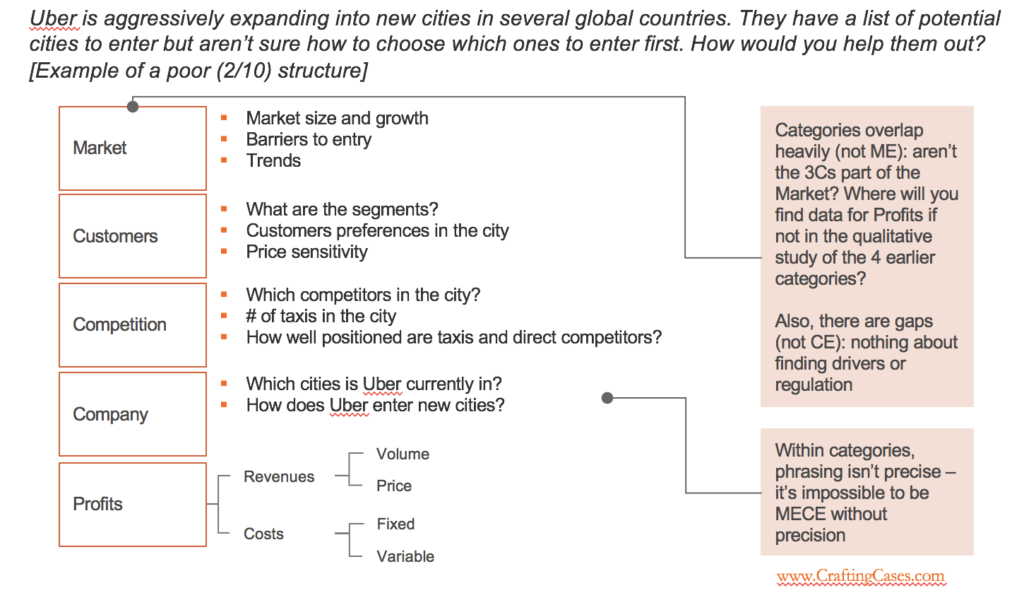

Our first example is on a case that looks deceptively simple: Uber is trying to figure out how to choose which new cities to enter with its service (try structuring this case before seeing the examples for turbocharged learning). To the unaware, it’s a generic market entry case that can be solved well using a generic structure. The wise candidate, however, knows no case is generic and each deserves its own custom structure.

The first structure is an example of a poor structure that isn’t mutually exclusive nor collectively exhaustive. PLEASE, don’t do the “mutually exclusiveness” mistake shown in the first box on the right! My guess is more than half of candidates who get to go to interviews do that specific mistake and most of them get feedback from the interviewer not to do it again. (note: you can combine qualitative and quantitative analyses into the same structure given that you communicate well, as seen on the second example).

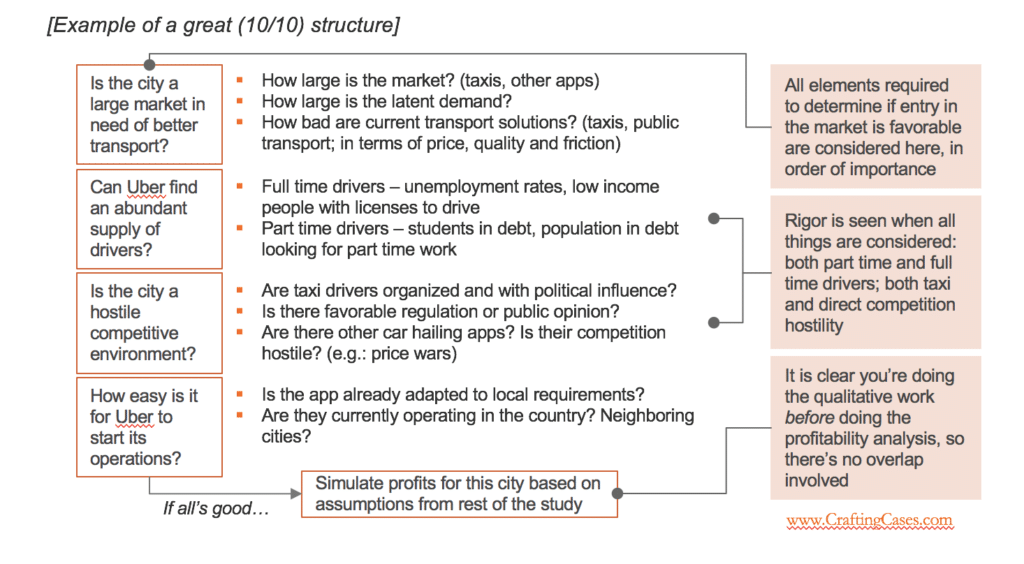

But what does a good structure to this problem look like?

Well, here’s a second structure that I would grade as a 10 out of 10.

It doesn’t necessarily take more time to build the great structure vs. the poor one to someone with the skills (I took roughly the same time to build each one of these structures). You’re going to notice that compared to the previous, weaker structure, this second example is both more clear and more precise. That’s what you get out of a MECE structure.

Ask an inexperienced analyst to solve Uber’s problems using the first structure and he will have trouble sorting which cities should they enter or not. He will be confused. The second structure gives a much more comprehensive and simple roadmap.

That’s what you’re aiming for. And that’s what MECE gets you.

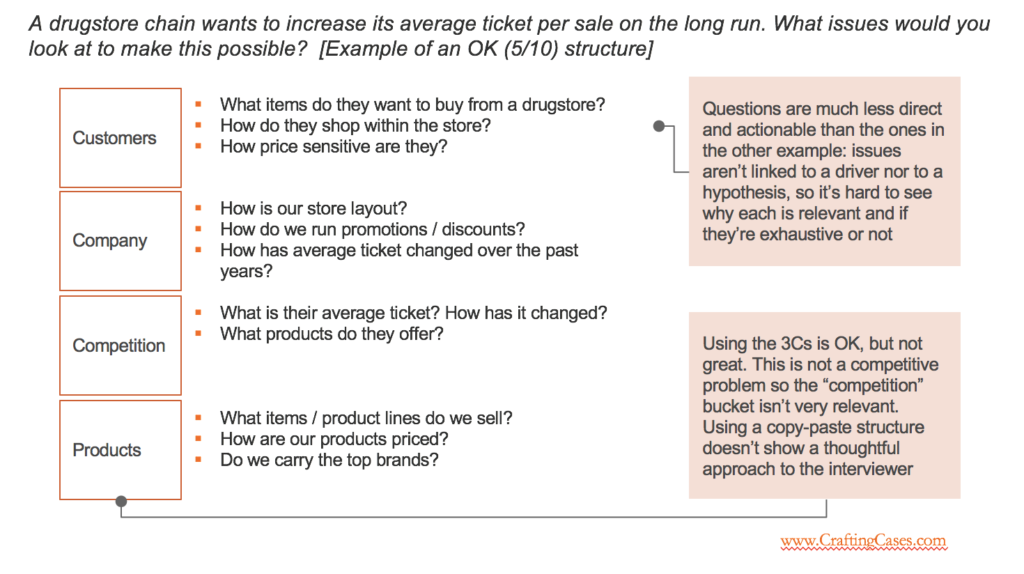

Let us check another example, now in the drugstore business. Suppose a chain of drugstores wants to increase average ticket per sale, that is, how much each customer spends per visit. They’re interested in the long run.

(Imagine you’re getting this question on interview day and structure on paper how would you answer this yo your interviewer before going ahead.)

I’ll give two examples of structure again, but the difference in quality between both will be smaller so you can get some nuance.

This structure is fine, and similar to what most candidates would do on interview day. I’ve seen coaching clients do exactly this. Unfortunately, though, most candidates never get the offer and this is what would happen to this candidate unless he was exceptional during the rest of the case.

The problem with this structure is that the categories are generic and the issues/questions within each aren’t very direct. You can’t really know why they’re asking each question and what would they do with the answer.

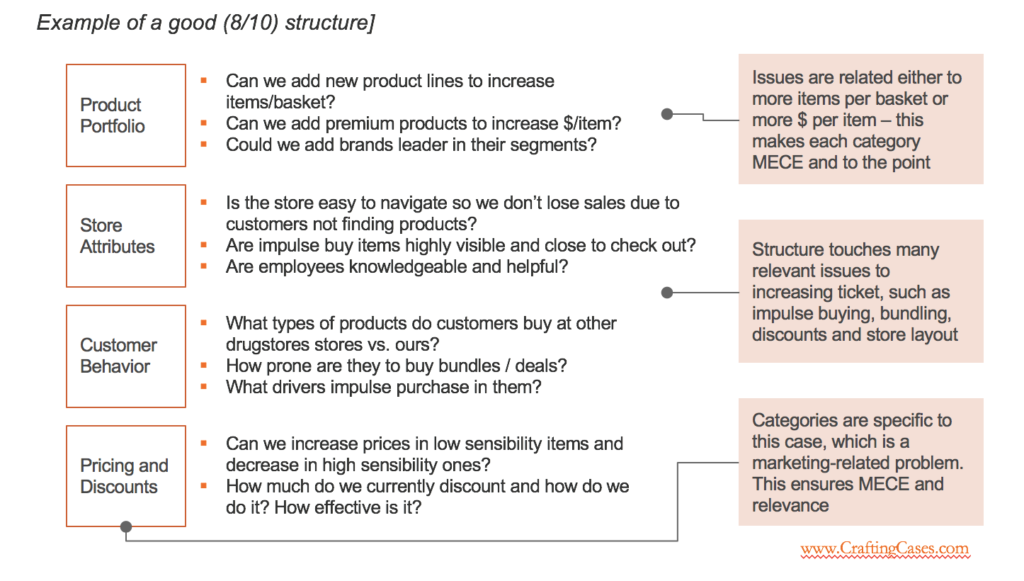

Let’s check a well-crafted structure for this case, then. Not the best, but one that’s reasonable for most candidates to learn to do in time for their interviews and that’s good enough to get the offer.

Here, the categories cover exactly the things that are relevant to solve this problem and the issues are much more definitive. You can know why each question is being asked, and so can the interviewer. And because the issues are so clear-cut, you can know how MECE the structure is. Being assertive and precise on the phrasing assures you’re solving the problem, being generic is avoiding it.

Not all MECE structures are made equal

If you’re exploring a region in different ways, you may want different maps. For instance, if you’re traveling by car, you’ll want a map of the roads. If you’re traveling by foot, however, a more comprehensive map with roads, trails and altitude differences would be more useful. A boat captain would be more interested in a river map that included both depth and navigability. If instead, your goal is to mine the region, you’d need a geological map. Different goals, different maps.

All of these maps are representative of the region and could be well-charted. No one map is more accurate than the other. In a sense, they’re all MECE. But if you have a specific objective and you get the wrong one, you’re asking for trouble.

The same goes for structuring business problems and case interviews.

You can create a number of different structures, all of them MECE, to solve the same business problem. But only a few of them will be actually useful. Some candidates go to case interviews using frameworks memorized from case interview books and are barely able to adapt them to the problem they get. Usually, their feedback is that the structure wasn’t specific enough, or that they lacked business sense, or that they couldn’t find important issues to the problem.

A good structure has to be MECE, but it should have other qualities as well. It should be relevant to the topic, it should approach the needs of the client with efficiency, it should be well prioritized. If you include these qualities as well, your structure can be better than MECE. MECE is a necessary but not sufficient quality of a good structure. A good rule of thumb to assess if your structure has these other qualities is to go through the toothbrush test: if the problem were in a different industry or company or situation, such as a project that involves selling a new brand of toothbrush, how much would my structure change? If your structure is so generic that it wouldn’t change much, you need to make it more specific. Otherwise, you’re just handing a generic map to someone in a unique situation and with a specific goal in mind.

Risk: the ultimate reason why you should always be MECE

Back to our original question.

Put yourself in the shoes of a big company’s decision maker. A Fortune 500 CEO, for example. You’re on the verge of making a huge billion-dollar decision. You decide to hire a top consulting firm to help you with that. What has driven this decision?

One factor is, possibly, that you don’t have the necessary staff to collect and analyze all the data that is needed for such a decision, so you have to outsource it to smart people. Another is that the consulting firm might have some unique knowledge you don’t possess. A more common factor, however, is that a one billion dollar decision feels risky. And management consulting is, in a way, risk insurance for decision makers.

A MECE structure guarantees the problem solving happens in a clear and rigorous way. And a good consultant needs clarity and rigor not for the sake of it, but because that’s what the client is buying: risk-reduction in the form of clarity and rigor (a third aspect is trust, but that’s for another day). The client is going somewhere and wants a reliable guidebook of how to get there and what to watch out for. Every good guidebook needs reliable maps.

If you’re going through recruiting in these firms, realize no one’s going to hire you if you can’t craft those maps. They will test it several times during the interviewing process.

But how can you make these? How can you create MECE structures for specific problems from scratch?

Well, through a combination of techniques I’ve described in a very detailed article series on how to be MECE and, of course, a lot of practice.

There are 5 basic techniques that guarantee a structure (or a part of it) is MECE. By combining those you’re able to create unique issue trees that will be specific to the case you’re solving. If I were to teach just one thing to people going through consulting interviews, it would be that, so make sure you read that article.

Also, let me know in the comments of a situation you had where being MECE saved your life in a case. Or worse, one that went wrong because you didn’t apply this principle to your cases.