Introduction

The Definitive Guide to Issue Trees

Issue Trees: the secret to think like a McKinsey consultant and always have a clear, easy way to solve any problem

Ask any McKinsey consultant what’s the #1 thing you should learn in order to solve problems like they do and you’re gonna get the same answer over and over again:

“You’ve gotta learn to create Issue Trees.”

Issue Trees (also known as “Logic Trees” and “Hypothesis Trees”) are THE most fundamental tool to structure and solve problems in a systematic way.

Mastering them is a requirement if you want to get a job in a top consulting firm, such as McKinsey, Bain and BCG.

But even if you’re not applying for a job at these firms, they’re a powerful tool for any job that requires you to solve problems.

In fact, Issue Trees are the main tool top management consultants use to solve the toughest multi-billion dollar problems their clients have.

This guide will teach you how to create and use Issue Trees.

I will give a focus on case interviews but you can use this skill in any other problem solving activity. I personally use it everyday at work.

(Which means what you’ll learn here is gonna be useful for far more than merely getting a job.)

About the author

I’m Bruno Nogueira.

I’m an ex-McKinsey consultant and I have learned to think using issue trees the hard way.

There were no good resources to learn this back when I was applying for the job.

Even within McKinsey there was no formal training. People just expected you to “get it” on the job.

After leaving the Firm, I’ve spent a few years coaching people to get a job in consulting, and I learned to teach this skill the only way possible: by actually teaching it!

Along with my partner Julio, I have taught 1000’s of people to break down problems in a structured way using issue trees.

And today I’m gonna teach you how to do this.

In this guide you'll learn:

Chapter 1:

Issue Tree Fundamentals

Issue trees are the blueprint of how McKinsey (and other) consultants think.

They make your thinking process more rigorous and much, much more clear.

Unfortunately they didn’t teach you this well enough (if at all) in school.

They don’t even teach this in most Business Schools.

But if you learn to harness their power, you’re set to case interview success (and a career where every problem can be easily solved).

How I learned about Issue Trees

A bit of a personal story first…

I first learned about Issue Trees from a friend who was working in management consulting. It was back when I was applying for a job at McKinsey, Bain and BCG.

This friend told me Issue Trees were the #1 thing I had to learn in order to do well on the interview and land a top consulting job.

And so, the first thing I did was to look for examples of Issue Trees.

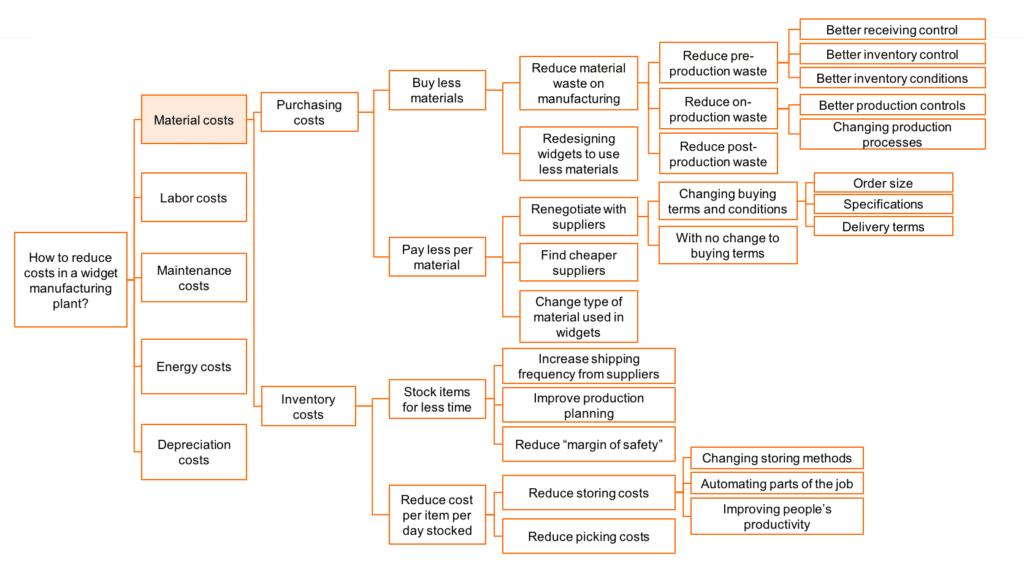

And I found stuff like this…

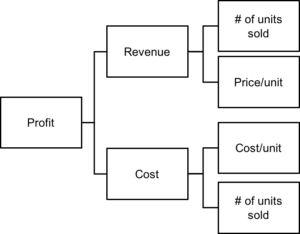

Not exactly rocket science, right?

But then I thought… “Alright, what if my problem is not a profit problem? Or what if I need to dig a little deeper than that?”

It didn’t take me long to find people on the internet telling me that you could use Issue Trees to solve any problem!

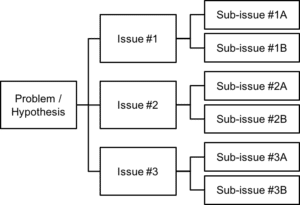

Here’s how they illustrated this important point:

Let’s be honest with ourselves here… This is NOT the best way to teach something!

And so I kept looking around.

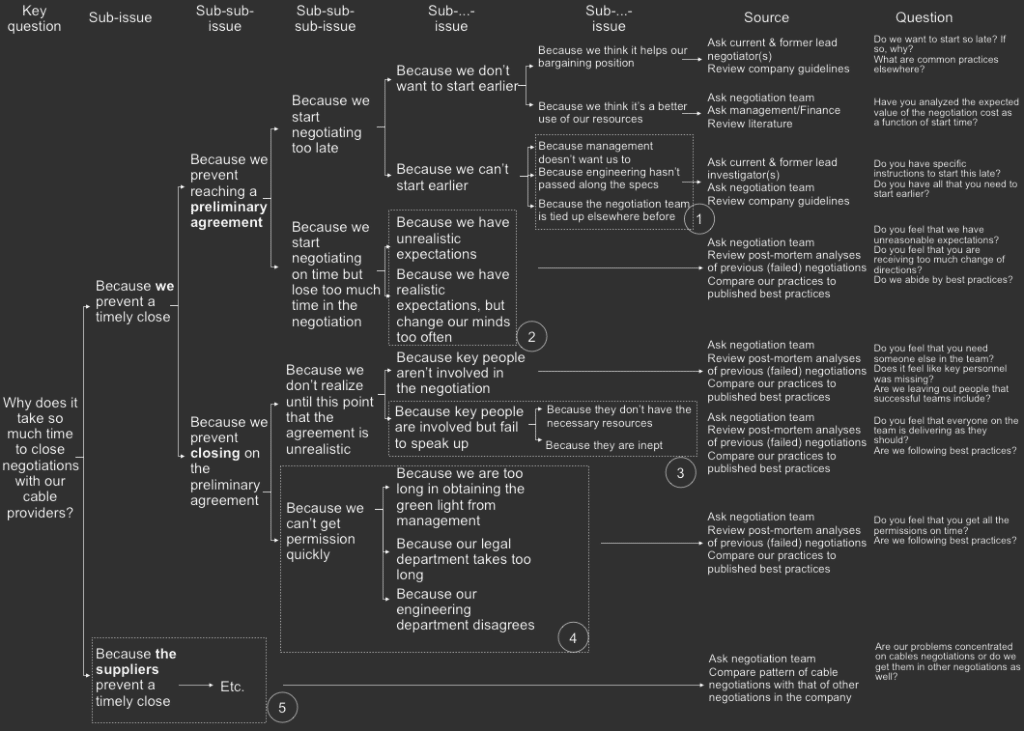

I wanted to see realistic examples of real Issue Trees consultants use to solve their client’s problems.

And if I was lucky, I hoped to find some explanation on why each example was structured the way it was.

Here’s the kind of stuff I found looking up on Google again:

And now I was left wondering how to get from Point A (the simple profit Issue Tree from the beginning of this orange box) to Point B (the behemoth you see above).

And I also wondered if getting to this behemoth was actually the kind of thing I wanted in the first place. Would it help me in a real interview?

So I gave up on the internet and decided to learn Issue Trees from those who know it best: real consultants. That’s who I learned to build Issue Trees from.

But I know that most people don’t have access to real consultants with the time to teach them things.

And it never stopped bothering me the fact that the internet had no decent resource to teach people of a skill that I use multiple times a day (and even make a living out of).

This is why I wrote this guide.

The 4 things you need to "get"

to understand Issue Trees

Before we jump into the nitty-gritty of how to create and use your Issue Trees, I want to give you a high-level view. This high-level view is what we’ll cover in this chapter.

I’m gonna show you four ways to look at Issue Trees so you can get an intuitive understanding of them.

And I’m gonna show you that through an example of a realistic Issue Tree.

1

They are a "map" of your problem

The first thing you need to know about Issue Trees is that they’re nothing more than a “map” of the problem.

Not just any map, but a clear and rigorous map.

We’re gonna achieve those two goals by using a principle called “MECE”. (Don’t worry about it now, we’re gonna get you covered later on).

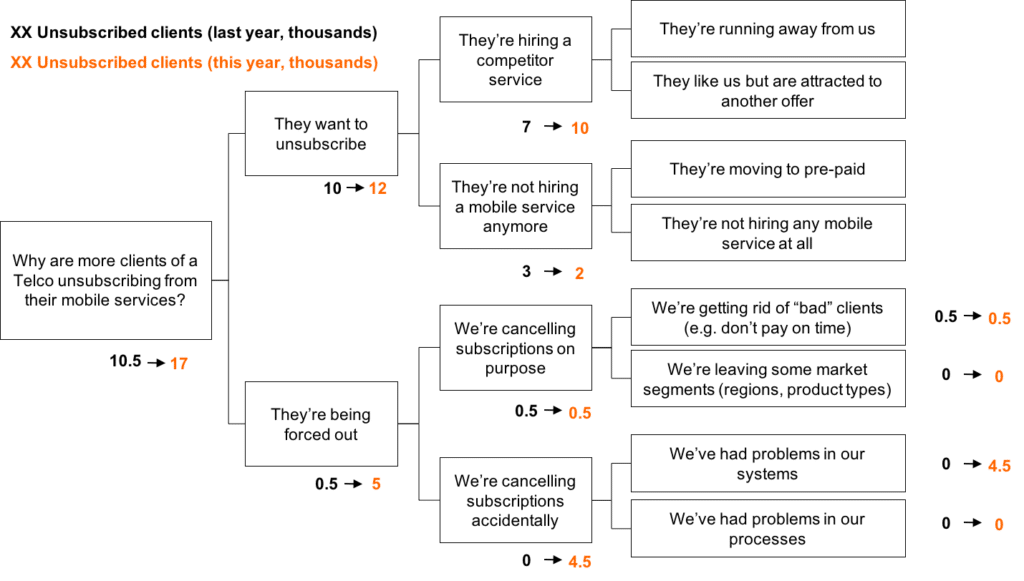

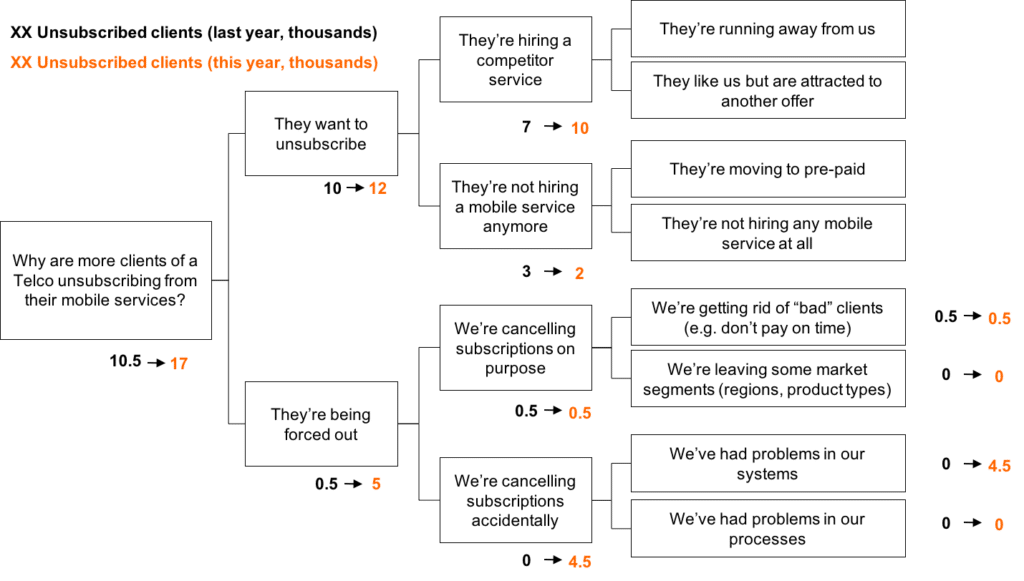

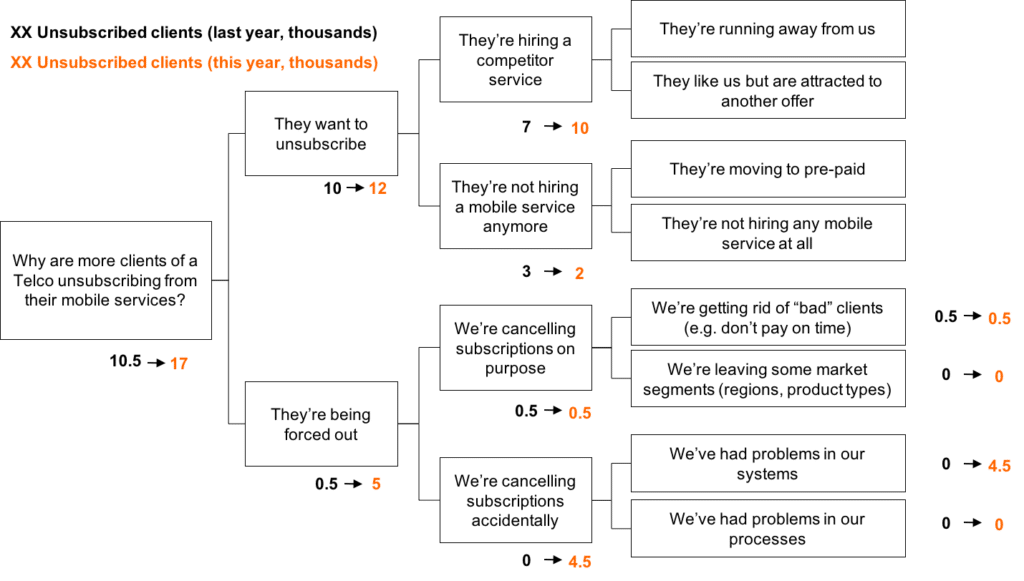

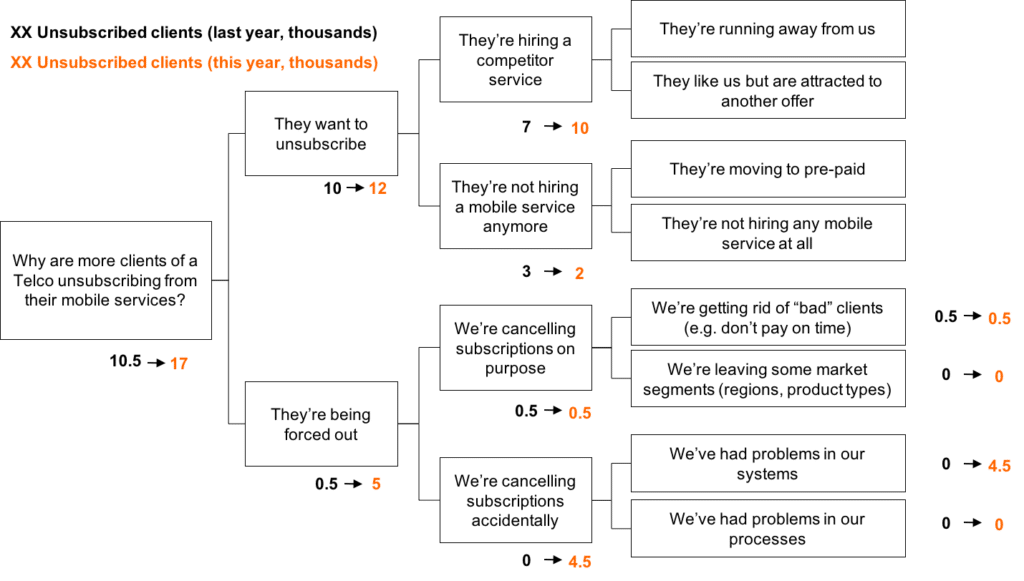

So suppose you’re an executive in a Telecom Company in charge of B2C mobile services (that is, cell phone services for regular people like you and me).

Imagine you have a client retention problem. That means too many clients are unsubscribing for your services/plans.

How would you figure out what’s causing this problem?

Well, a smart executive would build a “map” of all the possible things that might be going on. This map is your Issue Tree and “the things that might be going on” are your hypotheses.

I’ll show you one of these, but before I do that, I will ask you to do one 15-second task:

**Action step: grab a piece of paper and make a list of all the hypotheses that pop-up into your head of why customers might be unsubscribing for this Telco’s mobile services.**

Now, take a look at this Issue Tree.

If I did my job right, every hypothesis you had fits one of the “buckets” in this tree.

How do I know that?

Well, I used the MECE principle I mentioned above to build this tree. This means every “part” of the problem is here and that each “part” is different/independent from each other.

We’re gonna get back to this later.

The second thing to notice is that there are probably whole categories of problems you didn’t even think of when you wrote out your list of hypotheses.

You’ve probably thought about customers hiring a competitor service because they hate us for a variety of reasons (unreliable service, poor customer service) and you’ve probably thought about them leaving us because they were lured by competition somehow (low prices, free phones).

And if you’re savvy on the telecom industry, you might have even though about customers moving to pre-paid services.

But if my intuition is good, you have probably forgotten about at least a couple of categories within the “They’re being forced out” branch.

For example, you might’ve forgotten to think that they may be cancelling subscriptions on purpose because they’re leaving a market.

How do I know that?

Simple – I’ve done thousands of cases with hundreds of candidates to consulting jobs and most people forget about those.

The third thing to notice is that I didn’t even mention any specific hypotheses that you might have written on your piece of paper, things such as:

- We’ve increased our prices and our competitors have dropped theirs

- There were failures in our billing provider and a bunch of people were overcharged and got mad at us

- Our network was down for several days due to a problem within our IT systems, leaving people offline

- A problem in the banking system caused us not to receive several payments, which triggered subscriptions to be cancelled automatically

But still, all of these hypotheses (and thousands of others) would fit into one of the eight categories at the right-end of the Issue Tree.

All of this is to say that an Issue Tree is a map of the problem you have to solve.

Just like a good map it covers the whole problem area (you wouldn’t want a map of just a part of the territory you’re exploring).

And just like a good map, it doesn’t go into the slightest details (the specific hypotheses), but focuses on the broad aspects of your problem (the categories).

No adventurer should explore a territory without a good map.

And no smart problem solver should start solving a problem without a good Issue Tree.

2

Issue Trees are the tool for "dividing and conquering"

Issue Trees are more than a mere map. They’re a very useful one at that.

For those of you who are not warfare strategy geeks like me, “divide and conquer” is a military strategy based on attacking not the whole of the enemy’s forces at once, but instead, separating them and dealing with a part of their forces one at a time.

It’s much easier to deal with one cockroach a hundred times than with a hundred cockroaches at once (sorry for the nasty imagery for all cockroachofobics out there).

Anyway, this strategy goes back into the times of Sun Tzu (the ancient Chinese philosopher who wrote “Art of War”).

And it so happens that this “divide and conquer” strategy is not only good for dealing with military opponents, but also GREAT for dealing with Big, Hairy, Complex problems.

It’s very difficult to deal with a “customer retention problem” like our Telco Executive is facing right now without making this problem more specific first.

But if you try making it more specific without the help of an Issue Tree (or a “problem map”), you’re gonna end up with one of two things:

(1) An incomplete list of possible hypotheses (like the one you probably wrote down on your piece of paper)

(2) A HUGE list with hundreds, even thousands of hypotheses (which, at the end of the day, you don’t even know if it’s complete anyway)

Issue Trees allow you to divide the problem and work on it one part at a time.

Or, if you’re a Telco Executive like our friend from point #1, you can delegate this work to other people now that the problem is neatly divided.

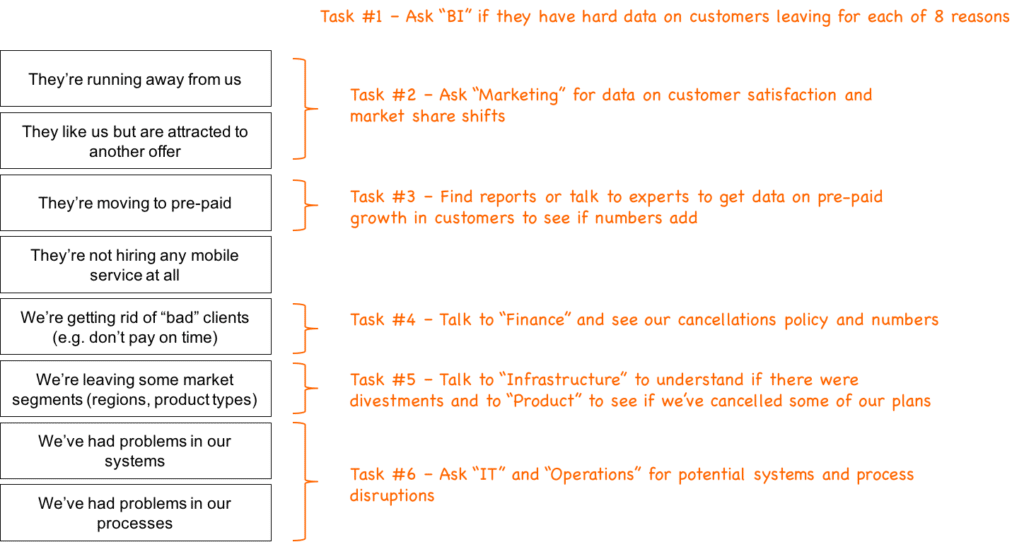

Here’s an example of how you can divide the problem into tasks and delegate its parts:

On the left side are the 8 buckets at the end of our Issue Tree. These are the eight potential problem areas.

And in orange are the six tasks our executive must do to know what’s causing the problem.

Many of them are actually just requests to other people within the company because when you use “divide and conquer” you get to give work to other people (which by the way, it’s a great way to grow your career quickly).

Depending on what they find Task #1, you may be able to stop there. Or you may need to do all 6 tasks and then some more as you find new, unexpected information.

Now, I know that this Telco Executive doesn’t seem like a really good professional when I put the Issue Tree and the tasks that way. He doesn’t even know the basics about what’s going on in his company!

But let’s pretend for a second that he was just hired and he’s not at fault for not knowing his company’s basic numbers.

Or that he’s actually a management consultant instead of an executive, and that he was hired to give this company’s executives an unbiased perspective of why customers are leaving.

Now things make more sense!

But the point is that the Issue Tree allows you to create a plan to solve the problem, just like a map allows you to create a route to get from Point A to Point B.

3

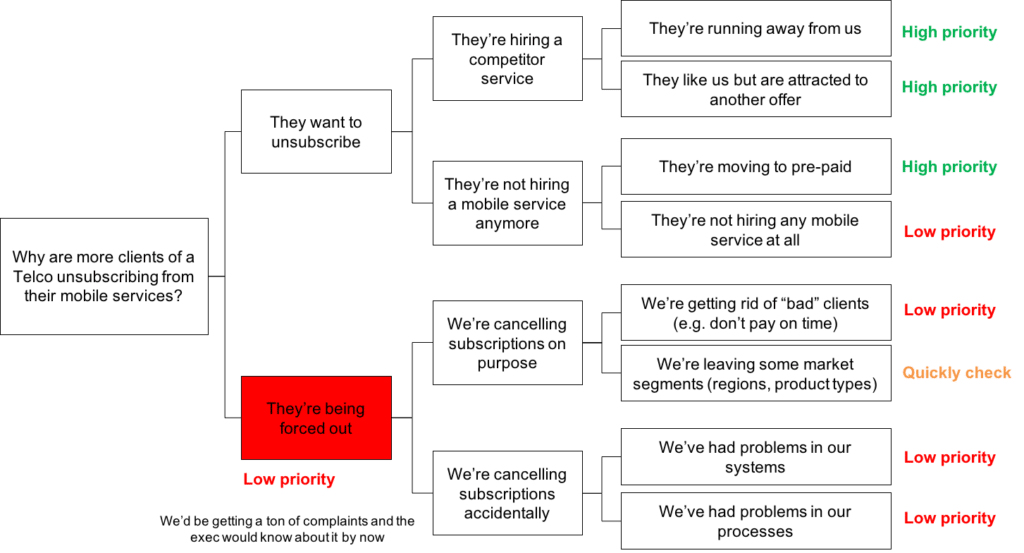

Issue Trees are excellent for prioritization

Not only Issue Trees let you have a “map” of the problem and help you create a “route” on how to solve it, they also give you the ability to anticipate a lot of stuff that could happen along that route.

And anticipation = prioritization.

(Or 80/20, for those of you who love the buzzwords).

Because Issue Trees lay out the underlying structure of your problem, they help you with two things:

(1) Get data structured in a way that helps you quickly find out where the problem is

(2) Anticipate what happened with a moderate to high degree of confidence even before you get data.

Let’s tackle each of these individually.

(1) Issue trees help you get data structured in a way that’s helpful to prioritize the problem.

Suppose you’re the Telco Executive and you’ve built your Issue Tree.

Remember how his Task #1 was to ask the Business Intelligence unit of his company for hard data about what’s going on?

Let’s assume they came back with the data below – how would you prioritize the problem?

The way I see it:

Of the 6.5 thousand extra people who unsubscribed this year compared to last year, the vast majority came (4.5) from a system failure. This is not acceptable and this should be the area this executive should tackle first.

But there’s also another area that calls my attention: our biggest source of customer churn – them going to competitors – has increased from 7k per year to 10k per year.

This person (and the company) has two different problems, and getting data in a structured format via the Issue Tree makes this very clear.

(2) Issue Trees help you make a really good guess of what might be going on even before you get any data

Suppose this company’s Business Intelligence division is not that intelligent and has no data to provide.

In fact, suppose this company has such a problem with data gathering that they can’t get structured data for pretty much anything.

This would make this problem a nightmare to solve.

With no structured data, this exec (or his subordinates) would need to do a lot of legwork to test each category of hypotheses:

- To know if customers are hiring a competitor service, we’d need to call a large sample of them and ask

- To know if a problem in our processes caused customers’ subscriptions to be accidentally cancelled, we’d need to map out all our processes that could’ve caused that and evaluate each one individually

You get the idea!

But Issue Trees are a map of the problem. And as any good map, we can use it to see what parts of the terrain seem to be more important than others.

Here’s an example of how to do that even if you have no data:

Obviously you need to use logical reasoning and a bunch of assumptions to prioritize one of these categories as more likely than others.

But in the absence of data that’s actually the best way to work!

So if I were this executive and there was no data, I’d try to work smart and start testing the most likely hypotheses.

This means I’d give more priority to the ones related to customers leaving us willingly.

It customers were being forced out we’d have crazy call centers full of customer complaints and the executive would probably know about it already. We’d probably have some lawsuits already!

I won’t go into the weeds of how to prioritize as we already cover that in our courses (including our free 7-day course on case interview fundamentals) but for now it’s cool to know that Issue Trees are the tool that enables you to prioritize effectively because it gives you a clear map of the problem.

4

You can have "problem trees" and "solution trees"

Last thing about Issue Trees that you must know to grasp what they are even before we can go into the specifics on how to build them is that you can have “Problem Trees” and “Solution Trees”.

Or, as I like to call them, “Why Trees” and “How Trees”.

“Why Trees”, also known as “Hypothesis Trees” are the one we’ve been working with so far.

You have a PROBLEM and you want to know WHY it’s happening. Then you create a tree with all categories of HYPOTHESES of why it happened.

Just like we did with our executive trying to fix the customer retention problem he is facing.

(By the way, this is why you can call them “problem trees”, “why trees” or “hypotheses trees”.)

But you can also use Issue Trees to map out SOLUTIONS.

This makes them really useful.

A consultant who can figure out what’s causing a problem every single time is a pretty good asset to the team.

But to have a consultant that not only can do that, but who can also figure out the best solutions to those problems every single time is even better!

So let me show you how a “Solution tree” or a “How tree” is different from a “Problem tree”.

Suppose our Telco Executive character did NOT have a customer retention problem. Everything is fine and clients aren’t unsubscribing from this company’s services more than the normal rate.

But, naturally, they still have some level of customer churn.

Let’s say that they want to make that level even better than it is today.

And then the executive team gets together for a meeting to “brainstorm” some ideas on how to reduce customer churn rates so they can grow revenues more.

What most people in this meeting are doing is to throw ideas on a whiteboard.

- “Hey, perhaps we can improve our customer service.”

- “Hey, maybe we should offer faster internet.”

- “Hey, what if we put people into long-term contracts?”

But our Telco Executive is smarter than that. He has learned how to make Issue Trees with his friend, a McKinsey consultant. And he puts his learnings into practice.

**Action step: grab a piece of paper and build an Issue Tree with the CATEGORIES of potential ideas/solutions this company could have to improve their customer retention.**

Now, word of warning: this “solution Issue Tree” is NOT perfect.

If you try, you can probably come up with an idea that could improve customer retention that doesn’t fit any of these categories.

And the reason for that is that it’s much harder to map out all types of possible solutions to a problem than to map out all types of possible causes to a problem.

But in case you do come up with an idea that doesn’t fit any of these categories, you can easily abstract what “type” of solution is this and then create a category for it.

Now, you might be thinking – “Bruno, why do I want to use Issue Trees for mapping out types of solutions? Why not just Brainstorm freely?”

There are three reasons for that:

(1) Your ideas are gonna be way more organized

This helps you communicate your ideas with others.

And it also helps you organize everyone’s ideas into a coherent whole.

And then better prioritize those ideas and even “divide and conquer” the implementation of them. You know, all the good stuff Issue Trees allow you to do.

(2) Creativity from constraints

This is counter-intuitive, but bear with me.

There’s significant research showing that having some constraints make people MORE creative, not less. (You can see some of the core ideas here, here and here.)

And we know that intuitively!

Wanna see?

Well, try to create a short story in your head.

Nothing comes to mind, right?

Now try to create a short story that involves an English guy, a French woman, a train trip and a few bottles of wine.

It’s actually easier to do the second, even though there are many more constraints.

Now, if I ask you to generate ideas on how to improve customer retention in a Telco company you’ll probably be able to generate 5-7 ideas until they start to become scarce.

But if I ask you to generate ideas on how to improve customer service in a Telco you’ll also be able to generate 5-7 ideas until they become scarce. Even though improving customer service is just a sub-set of the things you can do to improve customer retention.

And then I could ask you to generate ideas on how to make it financially costly to unsubscribe and you might be able to give me a few ideas as well.

Each of the last two questions was a branch of our issue tree from above.

And because our Issue Tree above has 7 different branches, if you’re able to generate 5 ideas for each, that’s 35 ideas!

I’ve never met a person that can generate that many ideas with just the prompt question (how to improve customer retention) and without building an Issue Tree first.

Our brains seem to get confused with that many ideas.

But if you add structure (forced constraints), you can think freely about each part without worrying about missing something.

Which leads me to the 3rd reason why you will want to use “solution Issue Trees” whenever you need to brainstorm ideas…

(3) They force you to see whole categories of ideas you wouldn’t have seen before.

This takes a bit of practice, but once you’re able to see how each category fits the whole, you might see parts of the whole that you weren’t even seeing before.

Take the “Make it costly to unsubscribe” category for example.

When I came up with it, I was thinking about financial costs. You know, contracts and stuff.

But when I saw the word “financial” coming up in my mind, I immediately noticed that there could also be “non-financial” costs, such as having to go to a physical retail store to cancel the service or losing your dear phone number that you had for 8 years and all your friends and business connections have.

I didn’t have these “non-financial costs” ideas before I create the category for them.

Which is another big advantage for using Issue Trees to come up with solutions for your problems. You can see the larger picture.

So, what’s our take away from all this?

Simple. Issue Trees are a “map” to your problem that help you prioritize what’s important and “divide and conquer” to solve it more effectively.

And you can use them to map out solutions as well.

Oh, and by the way, I almost forgot…

One really powerful thing you can do is to use “Problem Trees” to find the problem and once you found it, use a “Solution Tree” on your newfound problem.

So, remember how we used a “Why Tree” to find out that one of our Telco Executive’s problems was that his customers were leaving to the competitor?

Now we could use a “How Tree” to figure out potential solutions to stop our customers from switching to the competitors even though they don’t really like us and the competitor is offering a better offer than we are.

I’ll leave this Issue Tree for you to build.

And you’ll be able to build it using the techniques you’ll learn in the next chapter!

Chapter 2:

Three Techniques to Build Issue Trees

You can have all the theory in the world, but if you don’t put it into practice you’re not gonna solve any of the world’s toughest problems (nor get a job offer at McKinsey, BCG or Bain).

In this chapter we’ll go deeply into the mechanics of how to build quality Issue Trees.

More specifically, we’ll go through three practical techniques that you will be able to apply in your next case interview or executive meeting to structure any problem.

The structure of an Issue Tree

Issue Trees are a “problem structuring” tool.

That means you can structure problems using them.

But even Issue Trees have an underlying structure to them. It gets a bit “meta” and abstract, but the point is that every Issue Tree shares some similarities with other Issue Trees.

Knowing these common characteristics is the starting point to being able to successfully build them, so I’m gonna go over that in this short section.

And I’ll be quick, I promise.

(Note: I’m gonna give names to some stuff so that you and I can talk more effectively over the rest of the guide, but you don’t have to memorize those names nor use them in case interviews.)

And you can make some areas of your tree deeper than others.

But each part must FULLY explain the previous bucket from the previous layer.

To do this you use the MECE principle.

So we seem to always keep coming to this MECE thing, don’t we?

We have a whole article series on that, and I highly recommend you to go through it.

You can do so right now and then come back to this guide or you can read this guide first and then go there to understand how to make each part of your Issue Tree MECE.

Now, I don’t want to break your reading flow here…

So, before you open a new tab on your browser and get into another rabbit hole, let me explain what MECE is in simple terms.

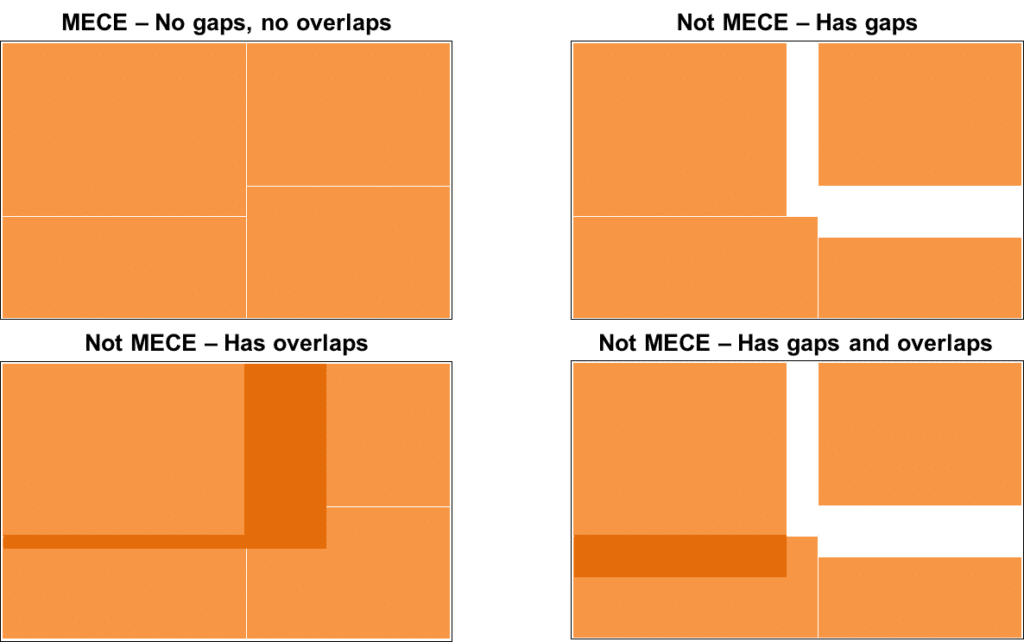

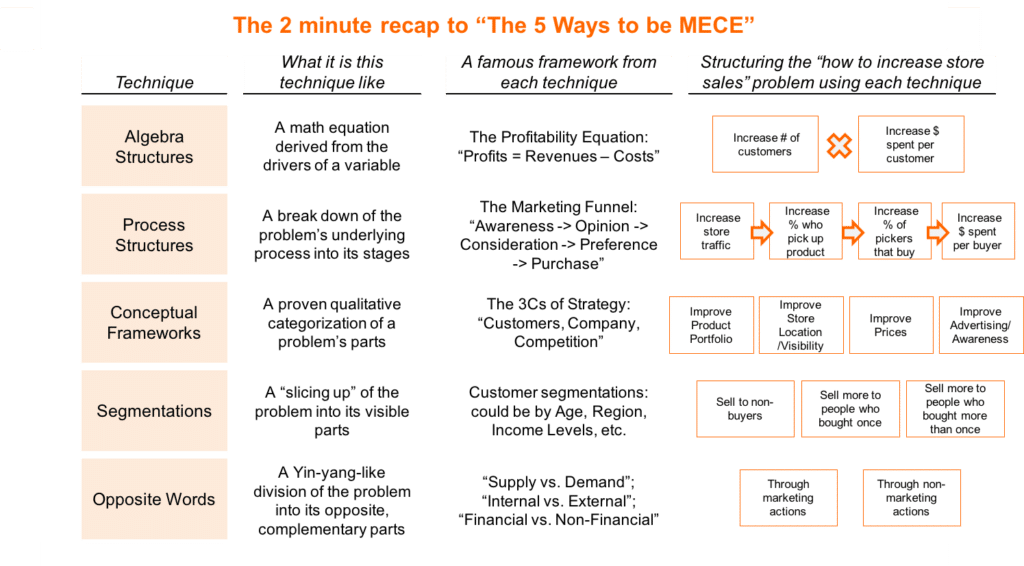

MECE means Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive and it is a basic principle of organizing ideas that was popularized by ex-McKinsey Barbara Minto (from the book on the Pyramid Principle, you might have heard of that) but goes back to the ideas of Aristotle (yes, the greek one!).

It basically means your reasoning has no gaps (Collectively Exhaustive, all parts together exhaust the whole) and no overlaps (Mutually Exclusive, one part is different and independent from the other).

Easy, right?

Well, kind of. Most problems out there are harder than drawing rectangles.

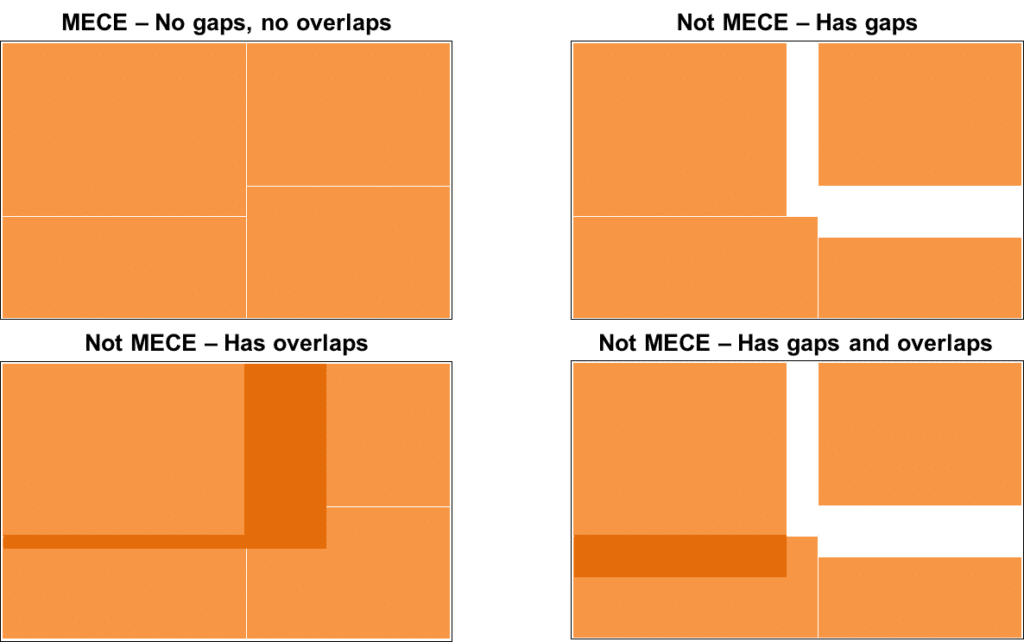

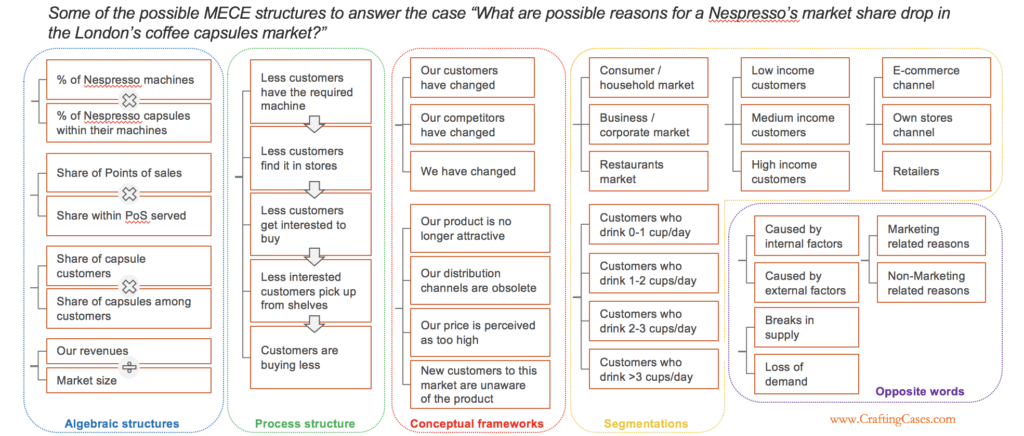

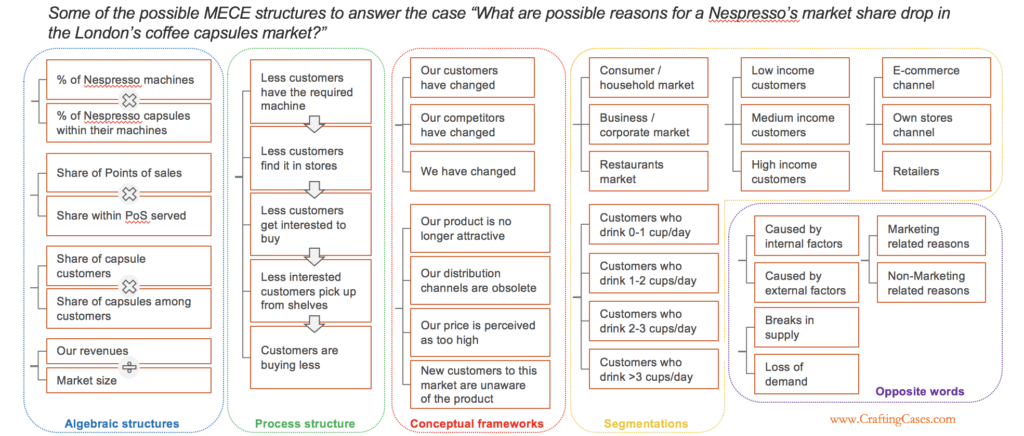

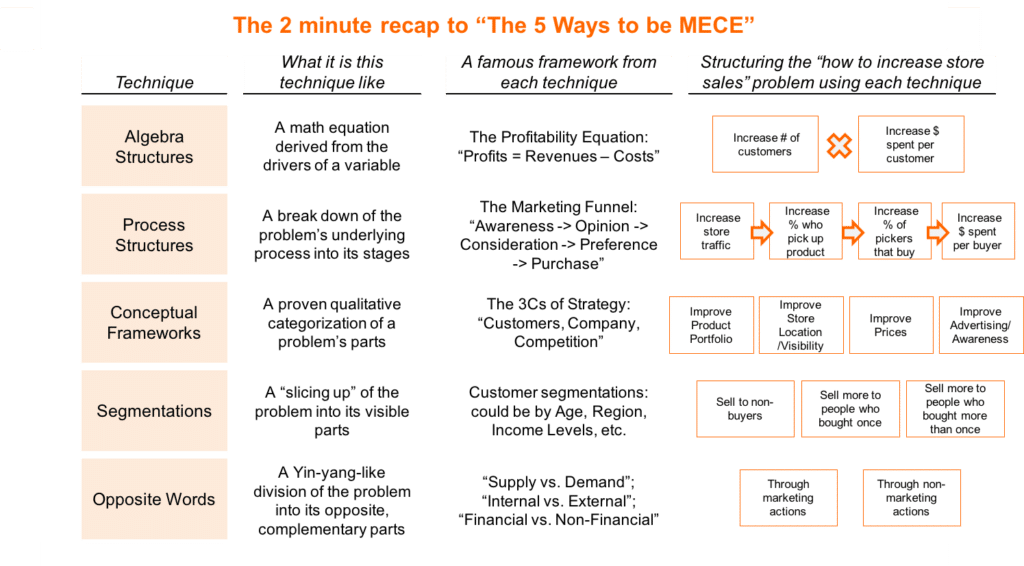

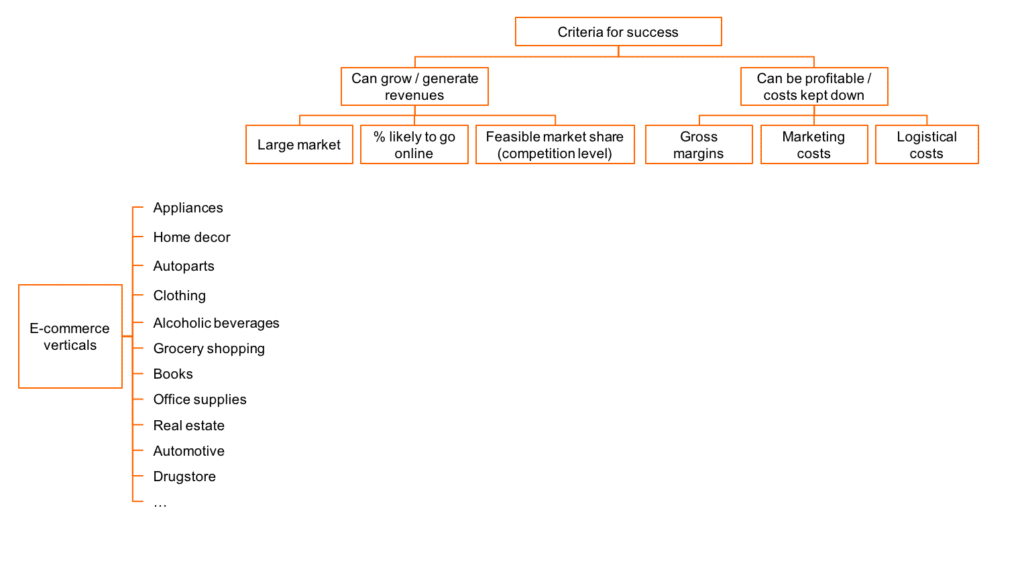

So, to give you a better idea of how to apply the MECE principle to a business problem, here’s an image from our article on The 5 Ways to be MECE of different MECE ways to break down the same problem:

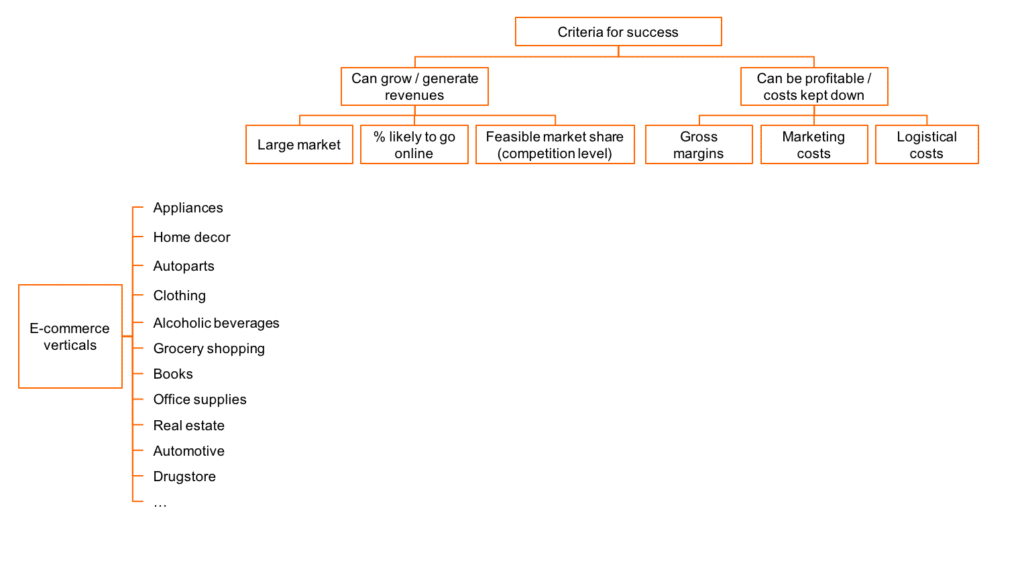

No need to worry about understanding this whole image right now, but the idea behind it is that (i) there are 5 types of ways to break down the problem in the image’s title (or any other problem) in a MECE way, and (ii) you can build different structures within each type.

An Issue Tree is built using a lot of these MECE structures. You also need to know how to pick among different options when you find more than one way to break down a problem..

I’m gonna link to the article on the 5 Ways to be MECE again because it’s the best way to learn about MECE in a practical way. Instead of a bunch of theory, I show actual techniques you can apply right now to any problem in that article.

Anyway, enough with MECE. Let’s jump into the actual techniques to build Issue Trees.

Technique #1: Create a Math Tree

Math Equations are ALWAYS MECE.

Equations have no gaps and no overlaps (otherwise they wouldn’t be equations).

Which is why I used rectangles within rectangles to explain MECE above. Rectangles are huge in mathematics if I remember my high school math right.

Anyway, one easy way to create MECE trees is to take advantage of that and ALWAYS break down the next level using a math equation.

Obviously you can only do that if your problem is numerical.

But since most business problems are numerical, we’re in luck!

I’m gonna show you how to do this in a “slideshow” kind of way because I wanna show you in a very step-by-step fashion, so be prepared to click on the arrow button more than a few times:

And each full layer is a complete equation of the variable that's being broken down.

Creating math trees as a way to create Issue Trees isn’t hard at all once you get some practice.

But some of its nuances can be deceiving. Most people see them done and think they can easily do it, but it all goes downhill when they actually grab a piece of paper and attempt to do these trees.

So, here are four methods to actually create your “mini-equations” to break down each bucket:

#1. Use a proven formula

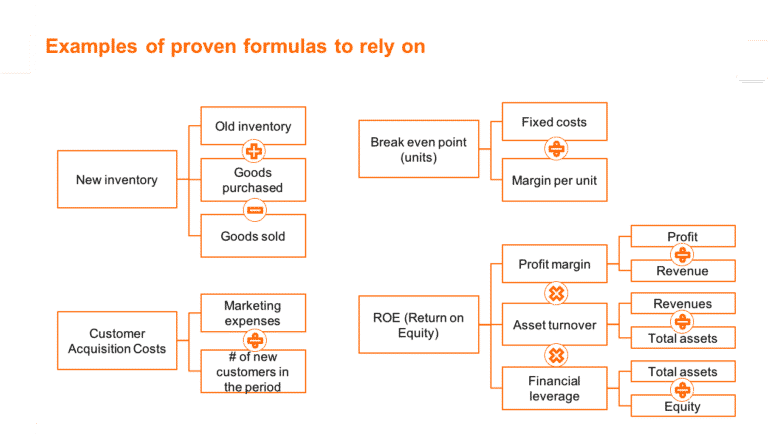

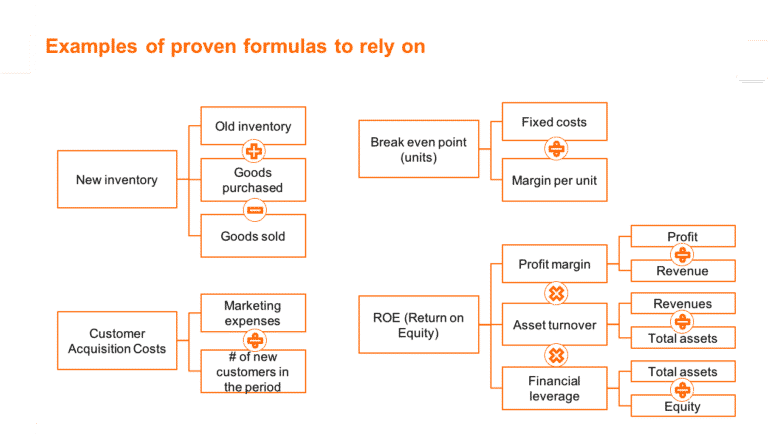

Most of the time you don’t need to reinvent the wheel.

If you know a formula that fits the problem well, just use it!

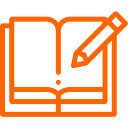

The most common one here is the classical Profits = Revenues – Costs, but there are others as you can see on the image below…

You don’t need to memorize any formulas for your case interviews, as you can use the other methods and they will work.

But knowing some of these, especially the most basic ones does help a lot.

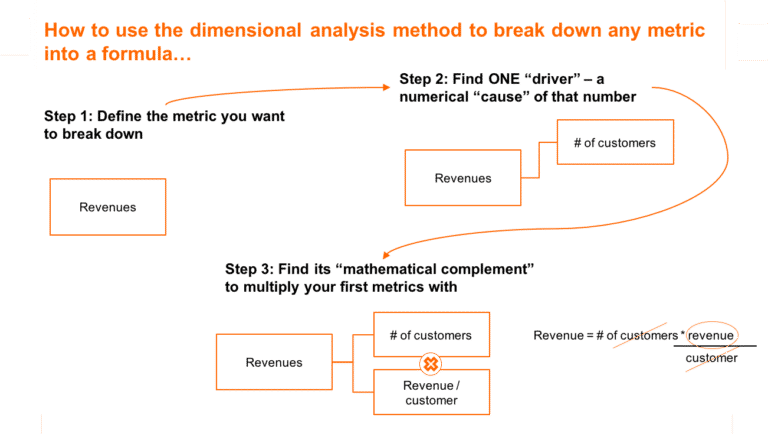

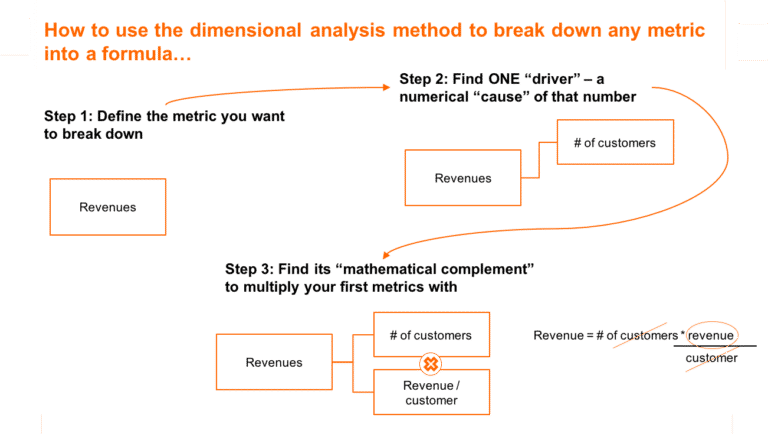

#2. The "Dimensional Analysis" method

This one’s my favorite!

Just find one direct “driver” of the variable you want to break down – a driver is a “fundamental cause” for that variable.

For example, one direct “driver” or “cause” of revenues is the “# of customers” you have. If you get more customers, these new customers directly cause your revenues to increase.

Then, use dimensional analysis to find its mathematical complement. If you want “REVENUES” and you have “# OF CUSTOMERS”, you need to multiply that by REVENUE/CUSTOMER.

Just like in your high school physics class, customers on the numerator will cancel out with customers on the denominator and you’ll be left with REVENUES as a metric – exactly the one you’re aiming for.

This method is amazing because it lets you break down almost any metric into a formula really quickly – the only thing to be careful with is to not lose meaning in the process and end up with a formula that is mathematically right but doesn’t make any sense to actual human beings.

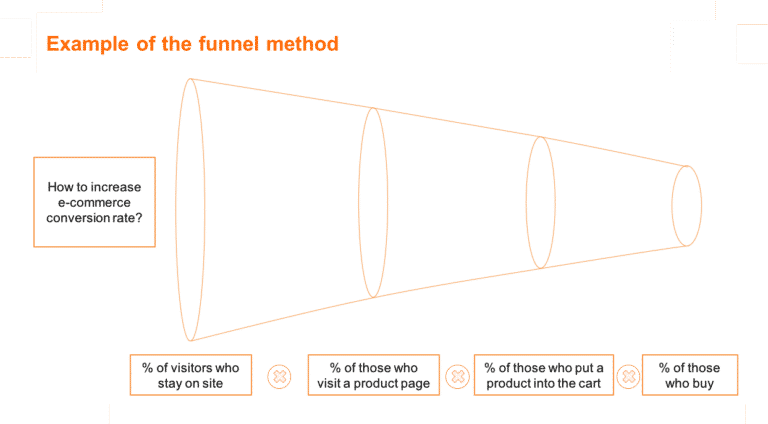

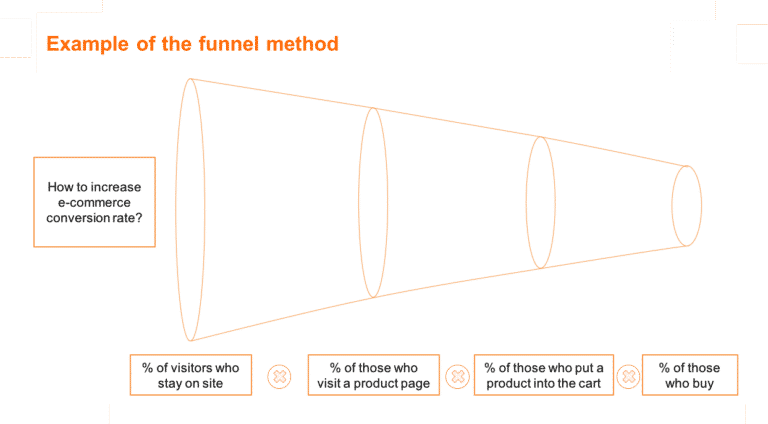

#3. The Funnel method

This works wonders when the target metric is a percentage or is the end result of a funnel.

Take one example from e-commerce: Conversion Rate.

This is the % of visitors in your website that buy from you. How can you break that down?

Simple, you multiply the steps of the funnel from visitor to buyer.

Funnels are everywhere: Sales, Product Development, Process Optimization.

All you have to do is to find these funnels and then break them into stages.

#4. Use a sum of segments

This is my least favorite method because it doesn’t go too much into the structure of the problem, but simply slices it out.

However, it can be useful.

For example, if you’re working with a conglomerate and their profits are down, it might be useful to segment that conglomerate into its different businesses.

Or if you’re trying to understand a company’s market share drop in a certain category, it might be useful to just break it down into the market shares of its product lines.

If you’ve read the article on the 5 Ways to be MECE and you’ve been paying attention, you might have noticed that method #1, “Using a proven formula” and #2, “Dimensional Analysis” will get you an Algebra Structure.

Method #3, “The Funnel Method” will get you a Process Structure.

Finally, method #4, “Sum of segments” will get you a Segmentation type of structure.

If you haven’t read the article, don’t worry about these names – they are some of the ways to be MECE we teach there. I’m just helping the folks who did read it already to make the connections.

So, summing up. You can use any of these four methods to create a “mini equation” and you combine these “mini equations” to create a “Math Tree”, which is the first technique to build and Issue Tree.

And it’s a technique that works great with numerical variables, but doesn’t really work if you have a different type of problem to solve.

So, to tackle non-numerical problems – or even to make better Issue Trees for numerical problems – let’s move on to the most powerful technique in your Issue Tree toolkit: layering the 5 Ways to be MECE.

Technique #2: Layering the 5 Ways to be MECE

Technique #1 works great because math is ALWAYS MECE and because creating equations isn’t too hard.

But not every problem is numerical and can be structured using equations alone.

And even to those problems that are numerical, doing a Math Tree isn’t always the best way to go about structuring them.

Here’s where Technique #2 comes in – instead of layering “mini equations” on top of each other, we’re gonna layer “mini MECE structures” on top of each other, regardless of them being equations or not.

Remember, we were confident to use math equations to build Issue Trees because they are always MECE. But from first principles what we need is MECE structure, not necessarily mathematical ones.

And where are we gonna find these “mini MECE structures”?

Easy, with the 5 Ways to be MECE. These are 5 specific techniques we’ve developed that guarantee a MECE structure.

I’ll make your life easier in case you want to read about that now and link to the article we wrote about them.

But here’s a quick recap:

The process of building Issue Trees by layering the 5 Ways to be MECE is itself very very similar to the process to create Math Trees.

Step #1: Define the problem specifically (no need to be a numerical variable here).

Step #2: Break down the first layer using one of the 5 Ways to be MECE.

Step #3: Get to the 2nd (and 3rd, and 4th) layers by breaking down each bucket into another “mini MECE structure” that comes from the 5 Ways to be MECE as well.

I’ll show you the exact process to create an Issue Tree by layering the 5 Ways to be MECE through the example below:

to define in this problem is what is "quality"

as a 1st layer and why?

Well, you could very well end your Issue Tree here.

Or you could dig a few more layers deeper. It really depends on the situation.

Click the arrow on the right to see what my next layer would look like.

Layering the 5 Ways to be MECE is my go-to method to create Issue Trees and break down problems or finding solutions.

I use it every day of my life, either on paper or just in my head.

And I used to use it everyday when I worked at McKinsey as well (even though I was doing it unconsciously – no one there had explicitly told me there were five ways to be MECE).

Now, let me address one thing that comes up often… One thing that may have crossed your mind as you were going through the three steps above regarding the Issue Tree is “well, but this is so obvious”.

That thought may have crossed your head in each break-down of a bucket or just when looking at the whole Issue Tree.

And here’s my take on it: a well-structured problem SHOULD look obvious – at least in hindsight.

How Elon Musk changes the world structuring problems in "obvious" ways

(I swear to you it’s interesting, but you can skip this green box if you want and/or understand why MECE Issue Trees are super important even when they’re “obvious”)

You’ve probably heard of Elon.

In case you haven’t, he’s this guy…

And he’s created these companies…

So, the guy basically transformed the payments industry, the automotive industry, the aerospace industry and is transforming the tunneling and the solar power industry.

But how does he do that?

Well, anyone who does that much has many “secret sauces”, but one of the special things Musk has is to think things from first principles.

In this fantastic blog post (from one of my favorite blogs), a guy who had access to Musk breaks down exactly how he thinks.

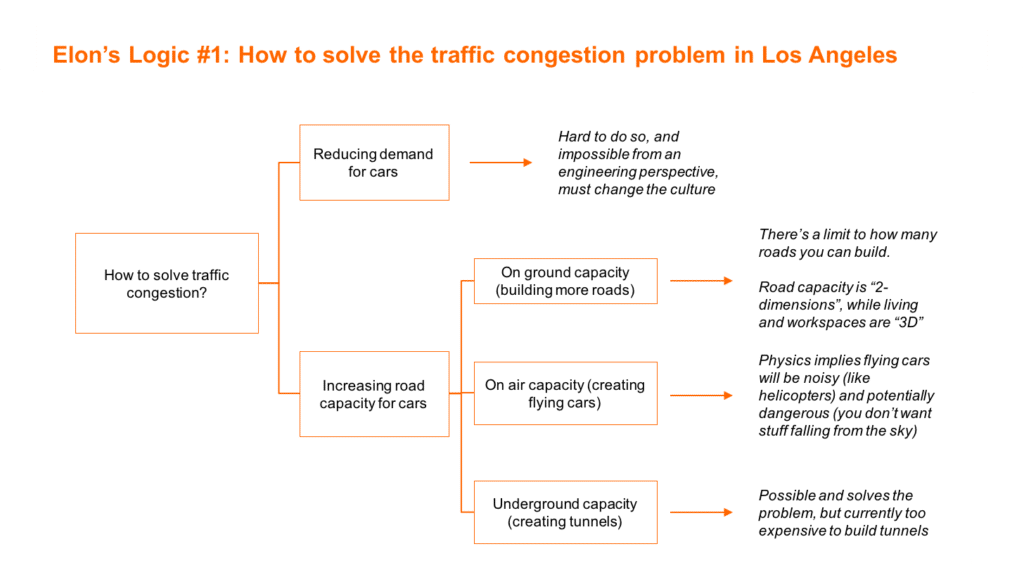

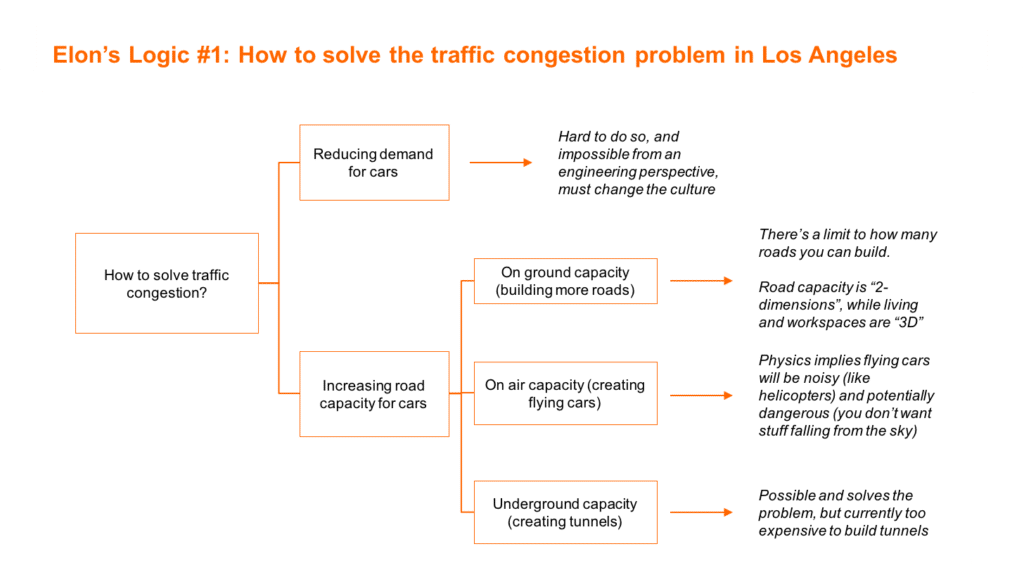

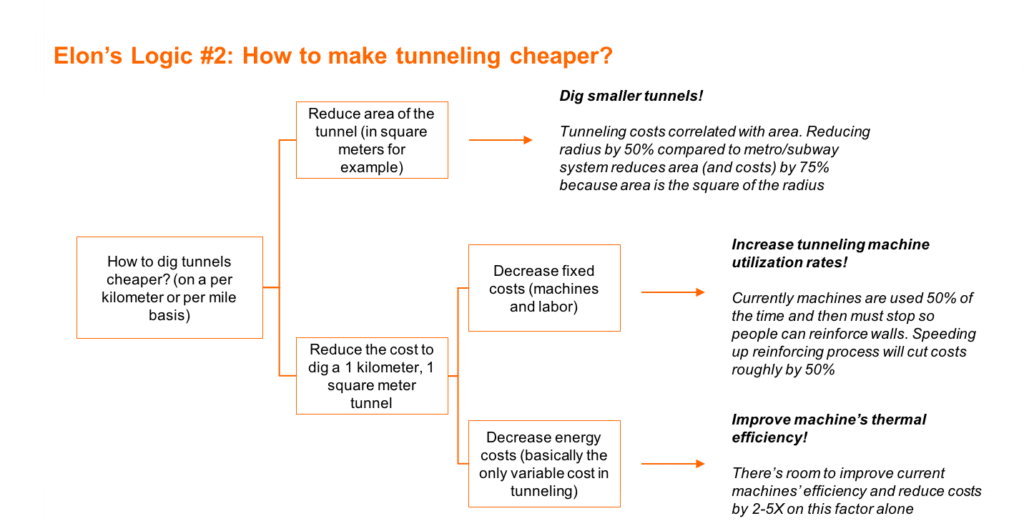

But let’s analyze one specific instance: how he came up with “The Boring Company”, a company that was created to dig tunnels more efficiently and solve the traffic problem in Los Angeles.

There are two underlying logics to the company:

Simple logic, but a really strong reasoning about why tunnels are probably the best way to solve the traffic problem.

(And it actually is the only way that’s ever worked so far – demand for roads keep increasing no matter how many Uber rides people take, building more roads doesn’t seem to make a difference in most cities and no one’s ever been able to make flying cars… But most people in large cities take the subway/metro system every single day.)

Notice that we’re basically dividing the problem into supply and demand and then dividing “road” capacity into on ground, flying and underground.

There’s no rocket science here (pun intended).

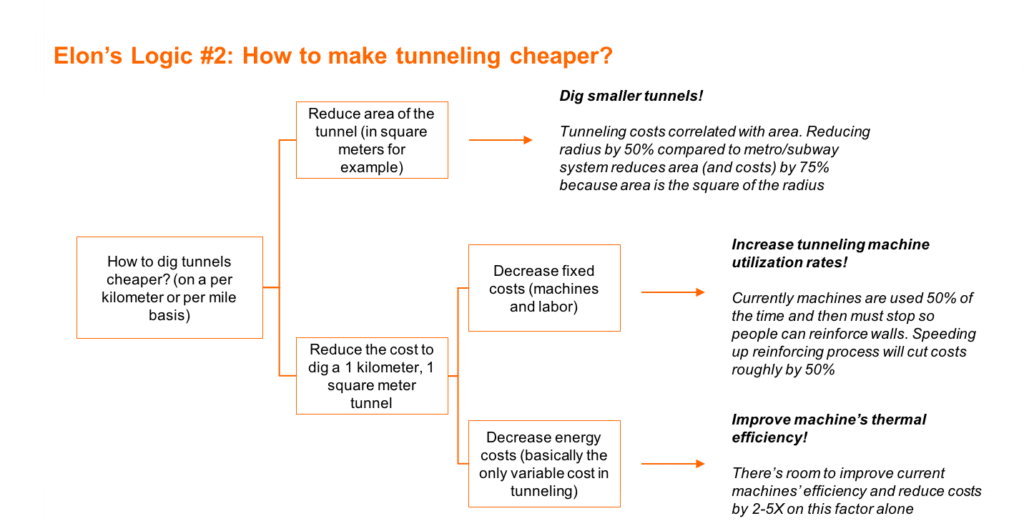

Alright, but there’s still a problem with tunnels: they’re expensive to make. So, is it possible to make them cheaper? Here comes Elon’s Logic #2 to build The Boring Company:

Again, no rocket science here (although a bit of tunneling science).

If you want to understand better how Musk thinks, I recommend this article and this TED Talk.

Now, onto what matters for us:

(1) Most traffic specialists know that trying to reduce demand is an uphill battle and that expanding road capacity is mostly fruitless.

(2) Most people in the auto/aerospace industry know that flying cars are a very far away dream

(3) Most people in the tunneling industry understand the cost drivers of a tunnel.

And yet, no one looked at the big picture and questioned things from first principles.

You need an Issue Tree to do that, even if it’s an obvious one.

I’m not saying Elon Musk draws Issue Trees for a living, but I know he has them in his head because he talks like he has one – I “took” both trees I showed you above from his own words.

Takeaway from the green box: Issue Trees are “obvious” because they’re drawn from first principles.

And this means if you want to think from first principles, draw Issue Trees.

Like what you read so far?

Share the guide on you favorite social media!

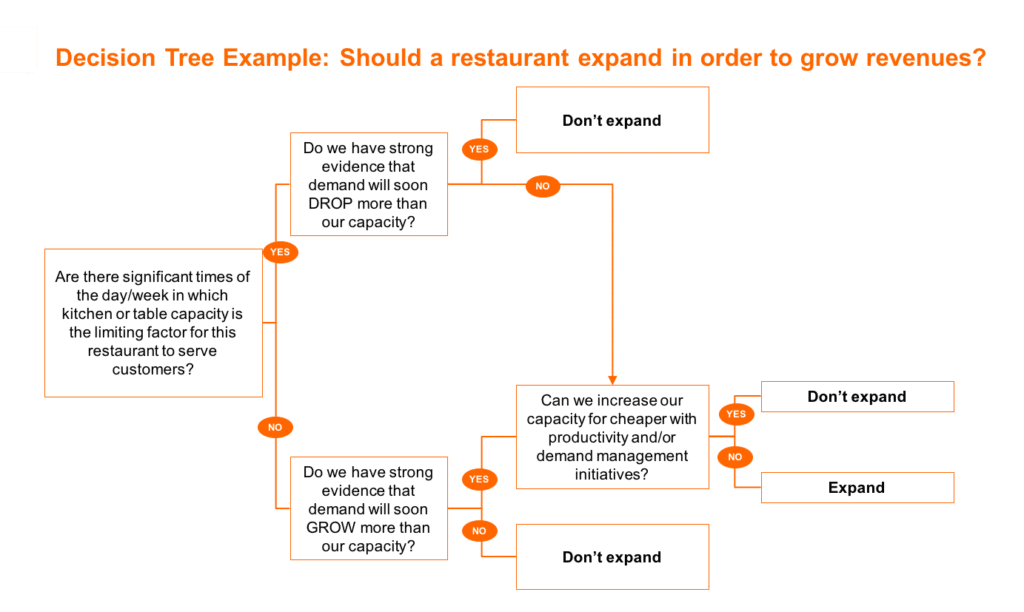

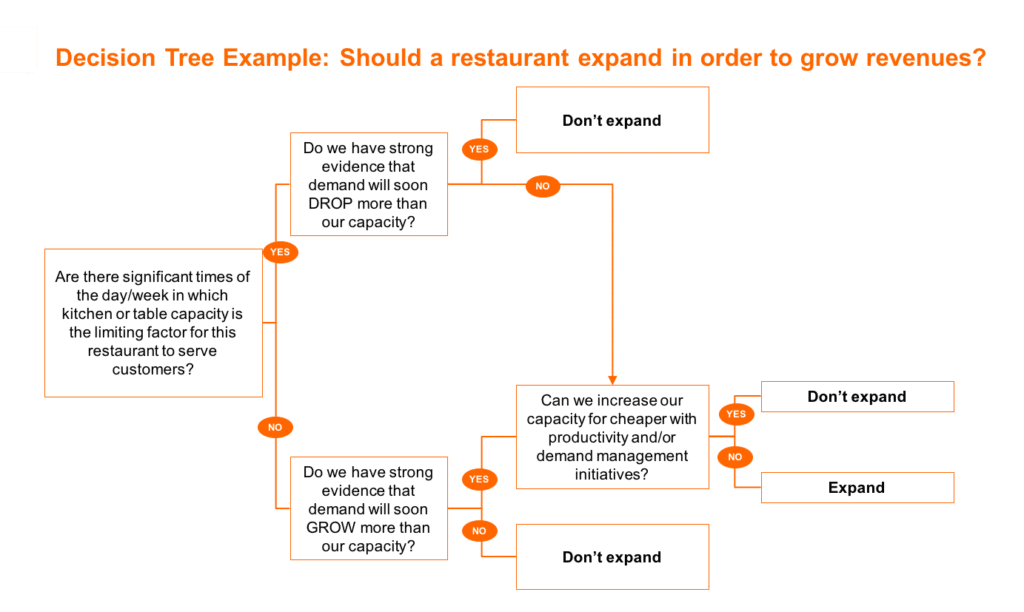

Technique #3: Creating Decision Trees

In the realm of Microsoft Excel, the most basic kind of logic you can do is using math operators. That is, adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing.

If you wanna go a step further you can use what they call “boolean operators”: AND functions, OR functions and so on.

And if you want to go a third step further, you can use “conditional operators”, the most famous of which are IF functions.

Decision Trees are basically regular Issue Trees with “conditional operators”, IF-THEN functions.

Now, let me translate into plain English for all the non-Excel nerds out there…

(Or should I say “future Excel nerds? I mean, this is a site for aspiring management consultants!)

When you do a Math Tree, the only way you have to relate the variables to each other is through math symbols. E.g.: Revenues = Price * Quantity. There is a mathematical relationship among everything in your Issue Tree.

It is great to have math because math is always MECE, but it is also limiting. What about everything that can’t fit an equation?

Enter Technique #2: Layering the 5 Ways to be MECE.

If you pay attention to it, everything that’s not in a mathematical relationship in that technique is joined logically by “AND” or “OR” relationships.

For example, we can find better employees ‘at the schools we already recruit in’ OR ‘in new schools’.

Another example, we can make new recruits better before their first project ‘by training them before they start’ AND/OR ‘as soon as they start working for us’.

Decision Trees are just like regular Issue Trees but they add another layer of logic to it: IF-THEN statements.

I won’t go into too much detail on how to build them because (1) it’s an advanced skill to be able to anticipate all the if-then logic required to take a decision before you even start exploring the problem, and (2) you don’t need to be able to do this to get a job at McKinsey, BCG or Bain if you can use the other two techniques well.

But I will give you a simple example below so you can see what I mean.

And if you want to learn more about this, here’s a timeless article from Harvard Business Review on Decision Trees.

There are also different types of decision trees.

For example, you can create a decision tree for an investment opportunity that considers the probabilities of different events to happen in order to calculate the expected value (there’s an example of this in the HBR article I’ve shared above).

Or you can create decision trees for WHY and HOW problems where you use IF-THEN statements to say where would you focus and prioritize if certain conditions applied.

(An example of the last phrase is this: in a case on “How should a restaurant grow revenues”, you can say that IF it has lines/too much demand, THEN you would focus on increasing capacity through expansion or increased productivity, and that IF if doesn’t have enough demand, THEN you would focus in customer acquisition and retention initiatives.)

Decision Trees can get really complicated even for simple decisions, so I would NOT recommend you to start learning with them.

Focus on Techniques #1 and #2 to solve WHY and HOW problems.

For “decision-making”-type problems, we recommend you to learn Conceptual Frameworks first. We teach how to structure these problems using Conceptual Frameworks in our free course on case interview fundamentals.

Want to learn to structure any case?

Issue trees aren’t the only technique to structure business problems.

Join our FREE 7-day course on case interviews to learn other techniques so you can structure any case, solve any problem and impress your interviewer!

It’s nothing like the other content you see around – just fill your name and e-mail and I’ll send you the link to join.

To get access to it, just go to our homepage and hit “Join now!”

Chapter 3:

Six Principles for AMAZING Issue Trees

Man does not live by bread alone.

And Issue Trees need more than being “technically correct”

If Issue Trees had a “soul”, it would live in the six principles outlined in this short chapter.

In fact, if you follow the principles from this chapter, you don’t even need to use any of the three techniques I showed you on the last chapter.

And if you MASTER these principles, you might be able to come up with your own techniques.

(And if you do come up with a “fourth technique”, please shoot me an e-mail telling me about it).

1

Separate different problems early on

Some restaurants that want to grow revenues should work on getting more clients. Others have too much demand and should work on expanding their operations to handle that and sell more.

Most companies that have employee attrition problem have some problem that makes people wanna leave their jobs. Others are just firing too many people.

And a violence crisis in a country could be caused by criminals. But it could very well be caused by a really violent police system as well.

The common factor between the last three situations is that each one could be caused by two COMPLETELY DIFFERENT PROBLEMS.

Separate them early on your Issue Tree because trying to fix the two things together will only lead to confusion. Not good.

2

Build each part ONE AT A TIME

Most people who see a huge Issue Tree for the first time are overwhelmed.

Of course they are!

They see this huge logical structure (that takes time to digest) and wonder if they’ll be able to do the same when they need to.

What they’re missing is that these trees are built one step at a time.

First you get the problem question and your only concern is to define it well.

Then your only concern is to break it down into a first layer.

Then you get each bucket from the first layer and your only concern should be to break each down into a “mini MECE structure”.

One bite at a time, you will eat the whole metaphorical elephant.

3

Each part must be MECE

I’ve talked about MECE before in this article, but I’ll do it one last time.

ME = Mutually Exclusive = No overlaps between the parts of your structure = your structure is as clear as the blue sky for another person to understand.

CE = Collectively Exhaustive = No gaps in the way you break each part of your structure down = your structure is rigorously correct.

MECE is tough for most people, but you can use the 5 Ways to be MECE as a checklist of structures you can use to be MECE.

That means it’s not gonna be as hard for you and you have more chances of getting the offer than the other people. Good for you!

4

Each part must be relevant and add INSIGHT to the problem

There are many MECE ways to break down any problem.

Choose the one that’s more relevant. The one that adds more insight to the problem.

For example, one of the Issue Trees from Chapter 2 was about improving the quality of new recruits in a consulting firm. Within “making the selection better”, I could’ve broken it down into “Stages 1, 2, 3” and so on of the selection process.

That would’ve been “technically correct” and “MECE”, but it would bring absolutely no insight to the table.

Why?

Because it wouldn’t be problem-specific.

Here are two resources to help you make your structures more insightful and problem-specific:

The first is a Youtube video on how to make better revenue trees. It shows how to create more insightful revenue trees but you can apply the same principles to any type of Issue Tree.

The second is “The Toothbrush Test”, a numerical measure so you can get a proxy of how insightful one structure is compared to another. You can watch the video here or read the article here.

5

Each part must be eliminative and help you FOCUS to the problem

An Issue Tree that is built in a way that allows you to ELIMINATE all the non-problems and focus on the one thing that’s driving the issue is way more useful than one that does not allow you to do that.

Say you’re a soft drinks company concerned that you’re selling less soda.

Here are two ways to structure the first layer of that Issue Tree:

(1) Drop in general soda consumption OR Drop in market share

(2) Customers less willing to buy product OR Competition getting stronger OR Company doing poor marketing or supply chain OR Distribution channels not exposing our product

Which one’s better?

Well, according to this fifth principle, (1) is better because it allows you to get data and eliminate a whole branch (unless the problem comes from both, of course).

Eliminative Issue Trees help you FOCUS the problem and waste less time (that means more 80/20 for you).

The key to be eliminative is to make each bucket FALSIFIABLE.

Falsifiable means you can find a test that, given a certain result, guarantees that the problem is not on that bucket.

This falsifiability is what makes Issue Trees “hypothesis testing” structures. If you want to be a hypothesis-driven problem solver you need to include falsifiability in your structures whenever you can.

However, this does not mean every single structure you create must follow this principle.

There are times where falsifiability is impossible, and that means you should focus your efforts in being the most insightful as you can (Principle #4).

It is usually in these situations where you’ll want to use a qualitative, conceptual framework. You can learn more about this in the free course we offer on case interview fundamentals. In the Frameworks module of the course we will show you exactly when to use conceptual frameworks and how to create them.by

6

Clarify what you need in each layer you build

You might be shy, but hey, overcome that shyness!

You don’t need to do guesswork to build your structures. You can ask first.

Actually, doing guesswork when you could’ve asked a simple question and eliminated confusion will harm your performance.

Say you’re breaking down how a consulting firm could hire better junior consultants. You’re trying to break down how they select candidates, but you’re not sure how their recruiting process is currently like…

Ask!

Say to your interviewer:

“Hey, I want to break it down into the stages of the selection process but I don’t know what those stages are. Here’s what’s on my mind… Does it make sense or did I miss something?”

If you’re doing Issue Trees to solve a problem in your work, this principle is even more important. You can’t structure what you don’t understand, so when in doubt ask questions and understand it better!

Sometimes these principles will enter in conflict with one another.

You might need to choose between being more eliminative and being more insightful.

You might feel in doubt of whether you should be fully exhaustive (MECE) or just add the relevant stuff.

And when principles enter in conflict, experience and judgement are here to save the day.

Seeing real examples of real people that know what they’re doing making Issue Trees to solve case interview problems is invaluable to get that experience.

Which is why I will show you in-depth examples in the next chapter, including videos of me going through the thought process of building Issue Trees with you.

Watch and practice real case interview structures!

Join our FREE 7-day course on case interviews.

You’ll learn all the techniques you need to apply the best practices to impress your interviewer (as well as why they’re looking for those traits).

It’s nothing like the other content you see around – just fill your name and e-mail and I’ll send you the link to join.

To get access, just go to our homepage and hit “Join now!”

Chapter 4:

Issue Tree Examples

When I was preparing for my case interview I looked for good Issue Tree examples all around.

I found none.

I don’t want you to go through the same, so here I’m gonna go all in and not only show you great Issue Trees but also show you, in video, how I think through each step of building them.

I’ll show you everything that goes through my mind as well as the specific nuances that make them great.

I will use different examples so you can see how the principles and techniques apply to different types of situations.

And I will do exactly what I’d do in a real case interview on when solving a real problem at work.

The only thing I’ll avoid doing is using Decision Trees.

Why?

Because it’s much much harder to get to a MECE result using them, let alone explain why it’s MECE. I’d be only showing off instead of actually helping you learn how the principles apply and what makes a great Issue Tree.

Not my style!

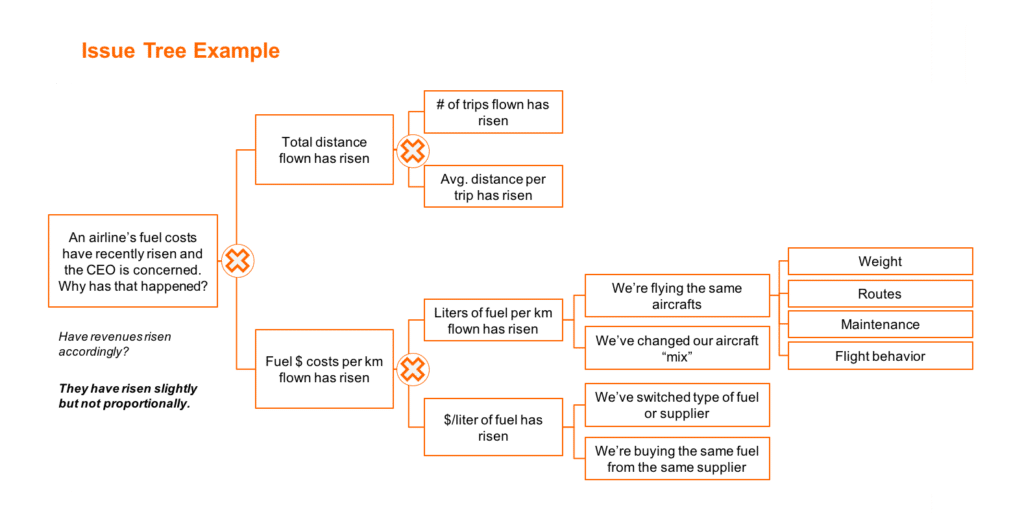

Example #1 - Airline fuel costs surge

This first example is of a fairly easy case question that would lead many well-prepared candidates to failure.

It’s funny how some problems can be easy to real consultants and yet hard even for candidates who have done 50+ cases.

Here’s why this happens: the business problem isn’t hard to solve from a first principles perspective (which is how good consultants tend to think) but they’re a bit unusual or too specific to an industry.

Most candidates who haven’t internalized the principles of solving problems well feel overwhelmed when they get a case completely unrelated to anything they’ve seen before.

Even worse is when this problem doesn’t fit the half a dozen frameworks these candidates have memorized by heart.

Here’s a video of this first example. I highly recommend you to try to structure this Issue Tree by pausing the video right after I clarify the case question and then compare your structure and your thinking process with mine.

If you don’t have access to audio or can’t watch a video right now, you’ll be able to keep reading and grasp the main insights as well, although I highly recommend you come back to watch this later!

So, what’s interesting about this Issue Tree example is that I have structured the first two layers of the tree as a Math Tree (Technique #1) and then I used the “Opposite Words” technique and the “Conceptual Frameworks” technique to build layers 3 and 4.

You can do that too!

Here’s the whole Issue Tree if you weren’t able to watch the video:

There were three main take aways from this structure:

Takeaway #1: Break down a numerical problem mathematically as long as the math remains meaningful/insightful – then get more layers using qualitative “mini-MECE-structures”

As with most thing problem-solving related, this is not a rule written in stone.

There are a few numerical problems that are best structured with a qualitative structure. And you don’t always need to do the qualitative layers afterwards.

But usually the best way to break down a math problem initially is to break it down into an equation first, as you’ll be able to quantify how each driver contributed to the problem.

And usually the equation alone won’t be enough to bring you to the meaningful stuff.

In this case, for example, if we were only mathematical in our structuring we would have missed important elements that show real world business intuition, such as “maintenance”, “aircraft weight” and “mix of aircraft in the fleet”.

Takeaway #2: Stop each branch when it can reasonably explain the source of the problem

I have stopped some parts of my tree in Layer 2, other parts in Layer 3 and others in Layer 4.

How did I make this call?

A lot of people have asked me this in the past: how can I know that my Issue Tree is done? How many layers do I need?

The rule of thumb is to stop when your buckets can reasonably explain the problem.

For example, on Layer 2 you have a bucket which is “# of trips flown has risen”. This can reasonably explain why fuel costs might have risen. It’s pretty logical – if you fly more trips, your fuel costs will rise as well.

Now, one could ask “why has the # of trips flown risen” and if that’s the actual problem going on, I as a consultant would want to know that. But that’s getting granular, you don’t need to go that far unless the problem is proven to be there.

If I told my mom or someone on the street that an airline’s fuel costs have risen because the # of trips have risen, they’d accept the answer and probably not question it further (and they certainly would tell me I’m a weirdo for caring about an airline’s fuel costs).

Now, if I told my mom or a random guy on the street that fuel costs have risen because liters of fuel per km flown have risen they would: (1) think I’m really really weird, and (2) not take that answer as it is.

Even if I used more accessible language and said that this airline’s fuel efficiency was down, they’d still ask me “why is it down”? (That is, assuming my mom is actually interested about airlines).

If I had stopped that branch on the 2nd layer, I wouldn’t be telling the whole story.

And so I went a level deeper.

Now, on the 3rd layer if I say that fuel efficiency is down because we’re using less efficient types of aircraft, most people would be satisfied with that answer. I can stop the Issue Tree here.

But in the case we’re flying the same aircraft, most people would NOT be satisfied. They’d be like “Hey, you’re telling me you’re less fuel efficient even though we’re flying the same aircraft? How come?”

And so we dig a level deeper on that one. Maybe the aircrafts are flying with more weight. Or we’re doing less maintenance. Or we’re flying at lower altitude and facing denser atmosphere. Or our pilots are changing speed all the time.

Most people would take any of those as sufficient answer. Which means we don’t need to dig a level deeper.

Takeaway #3: You can still go deeper in the buckets you need

If the last take away gives you an idea on where to stop structuring the Issue Tree, this one gives you permission to dig deeper than that.

Say your interviewer tells you the problem is that this airlines is flying their planes heavier and asks why that might be. Well, weight was at the end of our tree, right? But we can still investigate the reasons behind that increased weight.

Here I would segment the things that add weight to airplanes into their categories: people, cargo, equipment, fuel itself (we may be flying with excess fuel and thus spending more fuel to carry fuel itself).

Or say that the interviewer tells you that fuel prices have gone up even though we’re buying the same product from the same supplier.

Why that might be happening?

Well, either this supplier’s cost has gone up (because crude oil is up in price, for example) or their margins are higher (because we’re not negotiating as well, for example). We could dig deeper into each one of these factors if need be.

The point here is that even though you need somewhere to stop your Issue Tree (otherwise you’d spend the whole day building 15 layers), you also need to be aware that you can go as deep as you need to in the specific parts of your structure that the problem really is.

You find where the problem really is by getting data, numerical or not, for each part of your structure.

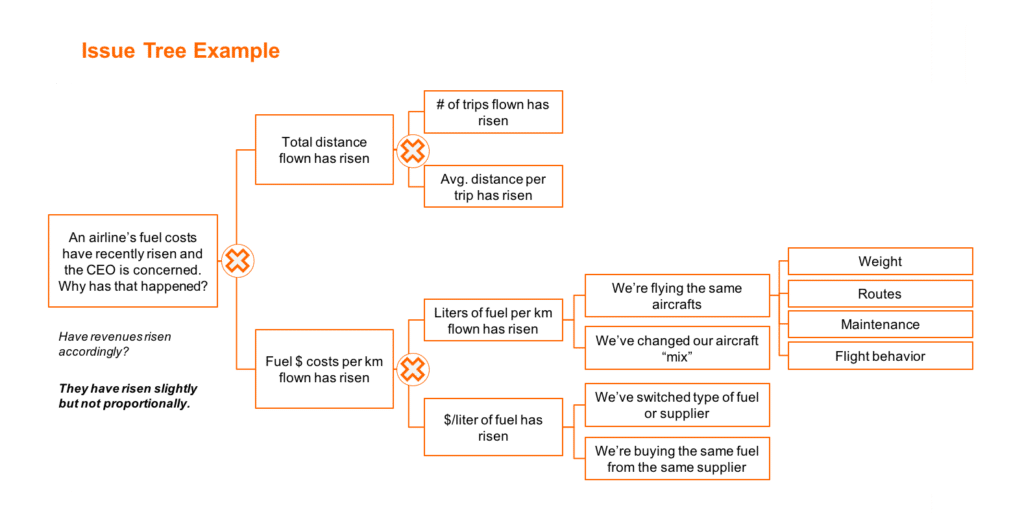

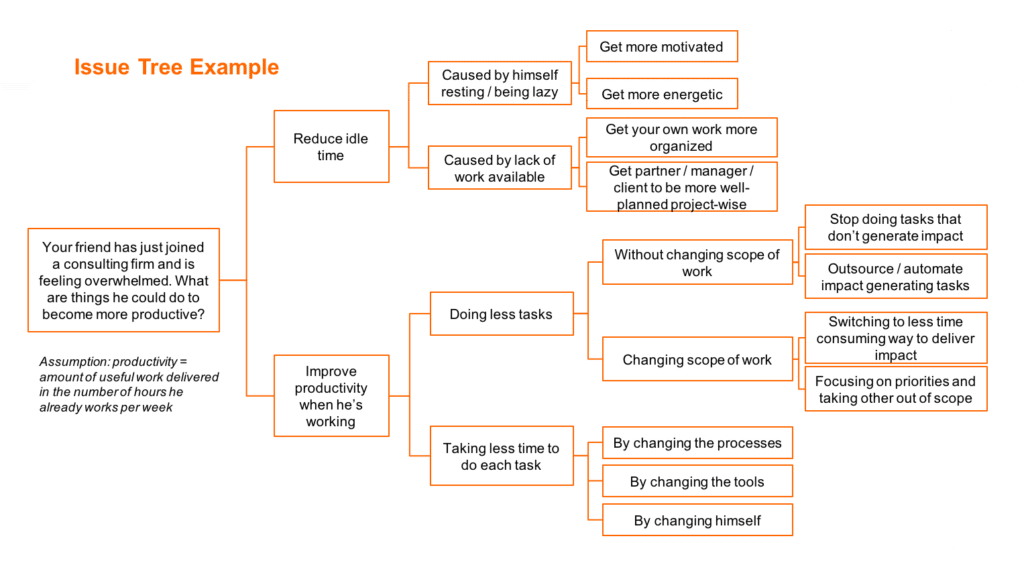

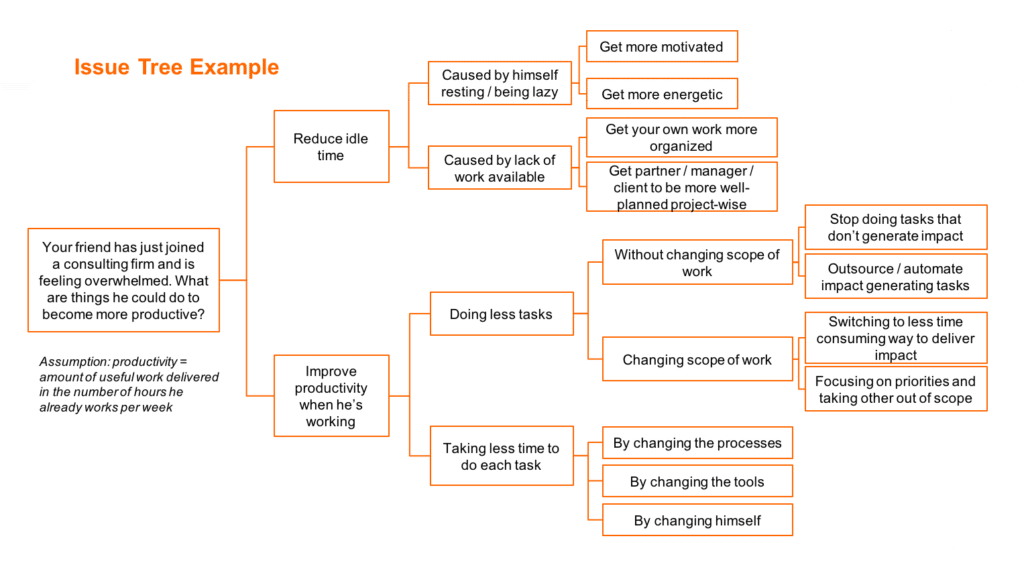

Example #2 - Overwhelmed consultant productivity

Real consultants have their own personal problems to solve as well.

And often time they will solve them with Issue Trees!

They’re a great way to see what your options are.

So before you look into this example, I want you to do an exercise:

**Action step: grab a piece of paper and write down all ideas you have to become more productive in case you were overwhelmed with work as a consultant**

What you’ll see from this exercise is that if you just “freely brainstorm” ideas to improve productivity on paper, you’ll end up with a huge list of (probably) unconnected action steps that are hard to estimate impact and to prioritize.

But if you had built an Issue Tree to organize those ideas, you’d get something much closer to an actual system to improve productivity.

Here’s what I mean by that:

This tree is solving a more qualitative problem than Example #1, but the techniques still work.

You define the problem really specifically at first.

And then you layer different “mini MECE structures” using the techniques from the 5 Ways to be MECE.

Here’s the final Issue Tree in case you couldn’t watch the video:

Of course your tree can still be different than this one and still be correct.

How do you know if it’s correct or not?

Well, simple: are you adhering to the key principles? Are you using the techniques I have shown you in this guide?

If so, your Issue Tree is good to go!

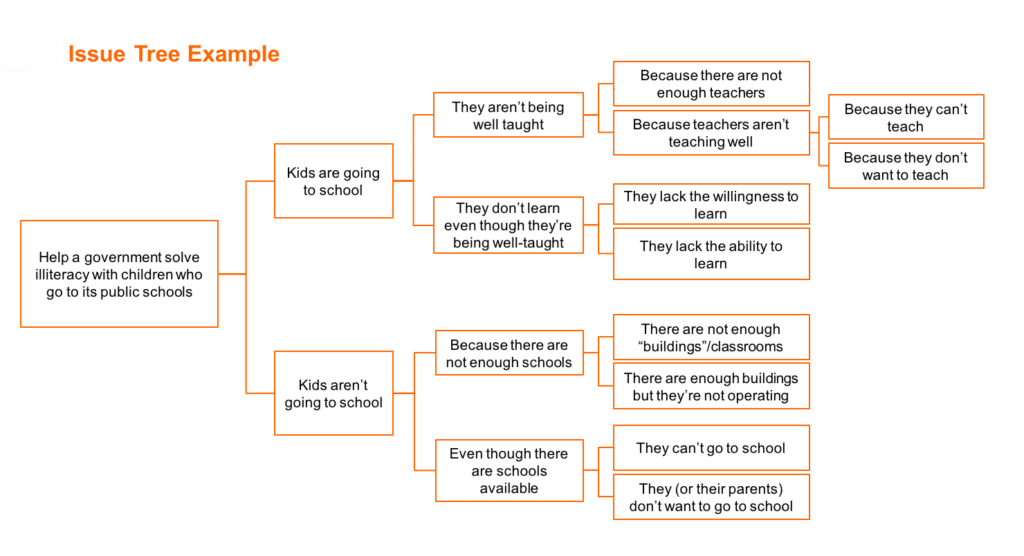

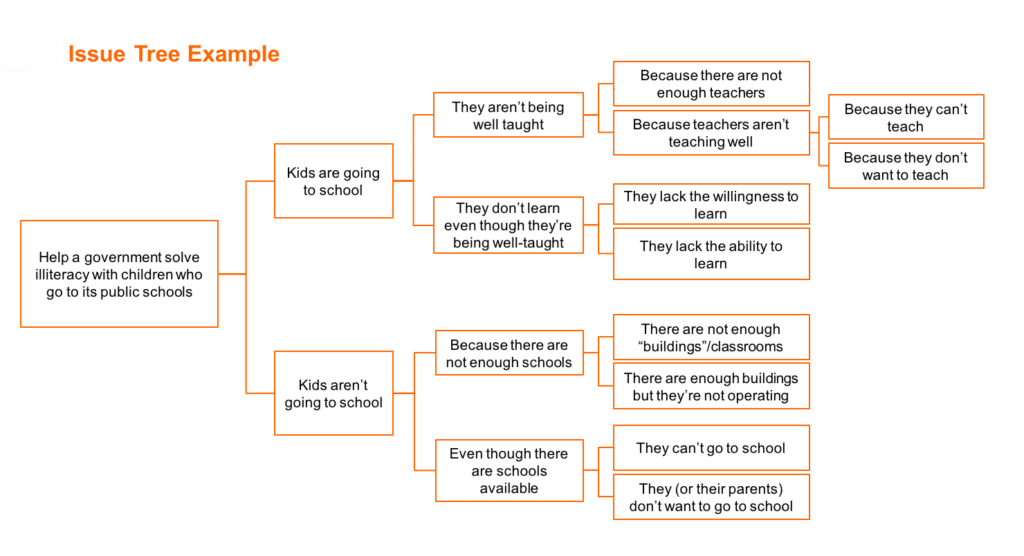

Example #3 - Help a government solve illiteracy in children

This is an interesting example because it focuses specifically on Principle #1: Separating different problems early on.

In fact, the whole Issue Tree is built by separating different problems over and over again.

Why?

Because the problem to be solved has many different possible root-causes that are completely different from each other.

Once you watch the video, you’ll see that the way the Issue Tree is constructed in a very intuitive way.

However, give this problem to most people and they aren’t able to structure it. They’ll spit out ideas and hypotheses without order nor an overarching logic.

Check it out how to help a government solve illiteracy in its children that go to public schools:

If you couldn’t watch the video, I’ll put an image of the Issue Tree bellow.

Notice how each layer is basically the previous bucket divided into two completely distinct problems.

The value of building Issue Trees like this is that you get a map of all types of possible root-causes. It’s also pretty easy to do so!

Friends help friends build Issue Trees...

Share the guide on you favorite social media!

Chapter 5:

Common mistakes and questions

I’ve helped hundreds of people learn to build Issue Trees.

In the process I’ve seen them making thousands of Issue Trees. And probably somewhere north of tens of thousands of mistakes.

Making mistakes if part of the learning process.

But you don’t have to make all those mistakes yourself because you can learn from theirs!

In this chapter I will show you the most common mistakes people make (with real Issue Trees, from real candidates) and also answer some of the most common questions that arise as you learn to build them.

What you can learn from the key mistakes of real Issue Trees from real candidates

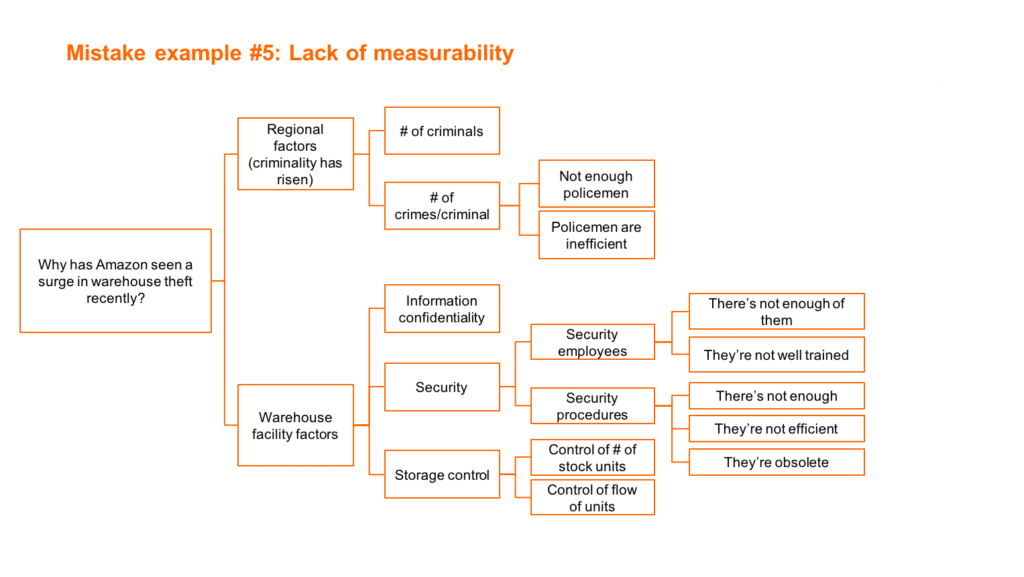

When I first wrote the 5 Ways to be MECE article I had a little challenge in the end of it.

I challenged people to send me a structure for a specific business problem that could happen in a case interview:

“Imagine you’re doing a project with Amazon and they’re complaining about a surge in theft in their warehouses – what could be causing this surge in theft?”

And so I got dozens and dozens of real Issue Trees from real candidates for the same problem.

What’s fascinating is that all these candidates had three things in common:

(1) They were having trouble with creating MECE structures for their cases (or else why would you read a huge guide on how to be MECE?).

(2) They had just read a huge guide with different techniques to be MECE and instructions on how to build Issue Trees using these techniques.

(3) They were dedicated enough to take my challenge, spend 10-20 minutes building their best Issue Trees and sending them to me.

Still, even with all those things going for them, most of their Issue Trees had mistakes. Mistakes you and I can learn from.

So in this section I’m gonna show you their trees, point out their key mistakes and show you the feedback I sent them.

#1 - Anastasia and the sin of ignoring problem definition

The first Issue Tree I wanna show you was sent by Anastasia.

Here it is:

Seems like a quite good Issue Tree, right?

I mean, it describes quite well the process of a warehouse.

Well, not quite.

There are a few mistakes that this Issue Tree makes in terms of MECEness, some parts could be more insightful, etc. But the most important mistake here is that Anastasia ignored the specificity of the problem.

Much of this Issue Tree isn’t about theft – it is about losing items in general. So she’s talking about damage, negligence, machine mistake, etc.

Go back to the image above and click the right arrow to see all the areas of this tree that are not about theft at all.

Most of the tree is not talking about theft at all!

What that means is that she’s talking a lot about things unrelated to the problem and leaving a lot of important things out. It also implies that she wasn’t listening to the problem.

This is the #1 thing I’d tell Anastasia to focus on and the #1 thing I’d tell you to make sure you’re not messing up.

Now, Anastasia’s structure also has a #2 thing that I’d tell her to focus on if problem definition weren’t a problem: look for root causes.

While she makes an excellent description of how the warehousing process is and thus is able to map out where the problem might be, she never talks about the why.

You know, things like security systems and lack of penalties and having warehouses in areas with a lot of crime. The types of things you might expect for a WHY question…

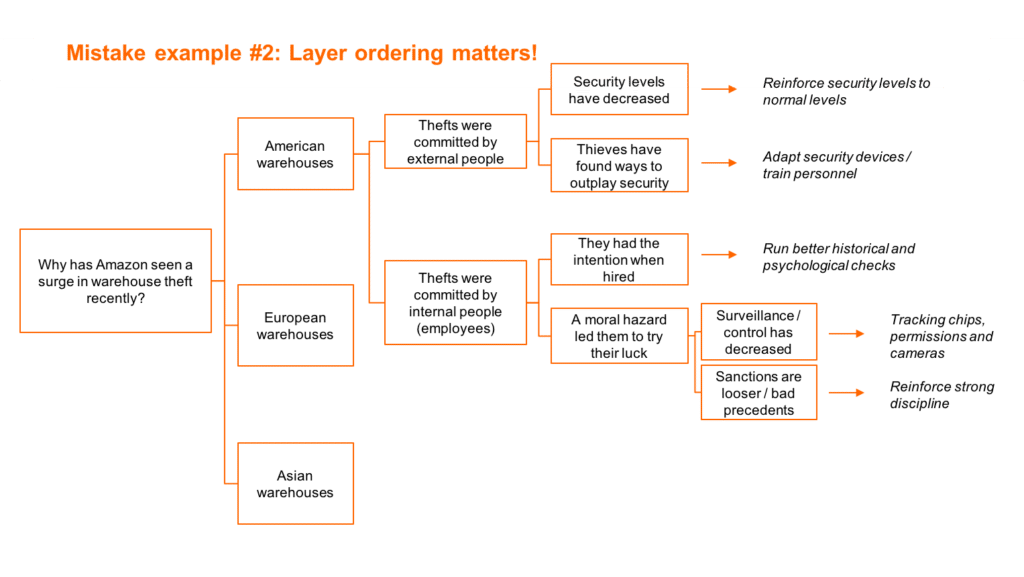

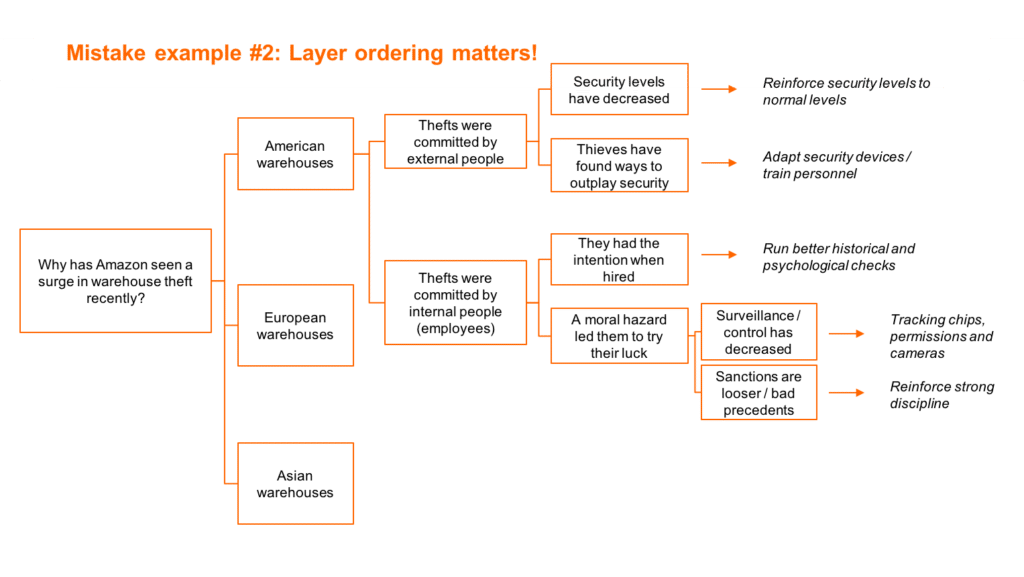

#2 - How Anne messed up with layer ordering

This Issue Tree is actually quite good!

But it has three main mistakes. Can you guess what they are?

Well, I gave you the main one in the title.

Anne’s first layer shouldn’t be a first layer.

Why?

Because geographical location is not all that important. The different geographical areas of the problem aren’t the most relevant way to break it down.

What’s more, even if it were, why divide by continent? Why not small vs. big cities? Or low income vs. high income areas? Or high-crime vs. low-crime areas?

Anyway, I think it’s an excellent idea to mention that you’d like to see in which warehouses is the problem more prevalent. But what I would’ve done is to put that as a side note to an Issue Tree that actually digs into the potential causes of the problem, not as the main course.

She could’ve done an Issue Tree of causes for one warehouse and then said at the end: “and then I’m gonna look at these causes for all warehouses we have, segmented by geographical area, warehouse size, how old they are, etc”.

And what would this Issue Tree that digs into the potential causes look like?

Well, very much like Anne’s example Issue Tree for American warehouses (which I guess she would replicate for other continents as well).

Now, you might be thinking: what are the other two mistakes she made?

Well, one is that she offered solutions to each root-cause of the problem. That’s not a mistake in itself. In fact, I loved it. But the problem is that she was a bit too early on that – she should’ve gone a layer deeper into the why each thing happened.

Keep in mind the case question was a WHY question and not a HOW question.

And what she did was to suggest, for example, that if internal thieves who had the intention of stealing were responsible for the surge in theft, then they should run better checks.

What she should’ve done instead was to say that if that was the cause, then that caused happened because (a) they’ve stopped doing background checks, (b) background checks have worsened in quality or (c) background checks were never good at stopping that but that was never a problem beforehand. And then perhaps dig even deeper into the cause.

But she offered solutions before she got to the root cause, and that may hurt because she may be solving the wrong problem.

And the last mistake she did was one related to problem definition.

Everything she mentioned was related to the amount of theft. But we don’t know if that’s the problem. It’s not clear on the case question (on purpose). Maybe the problem is the value stolen.

So, she would’ve done much better by showing that in her structure. Maybe there are more thefts (in which case her issue tree is valid) and maybe the amount stolen per theft is higher (and because she didn’t consider this, she missed a whole part of the problem).

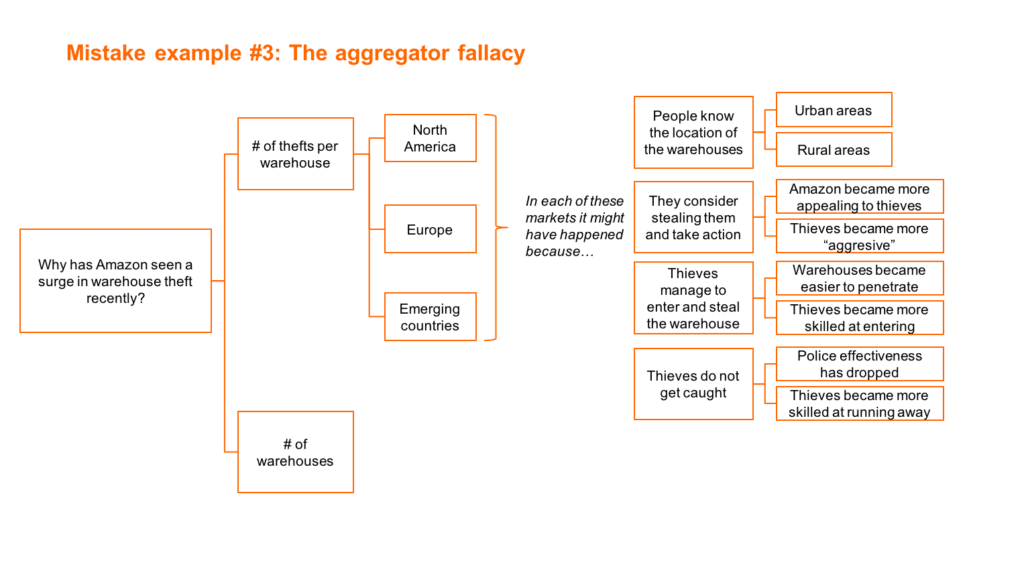

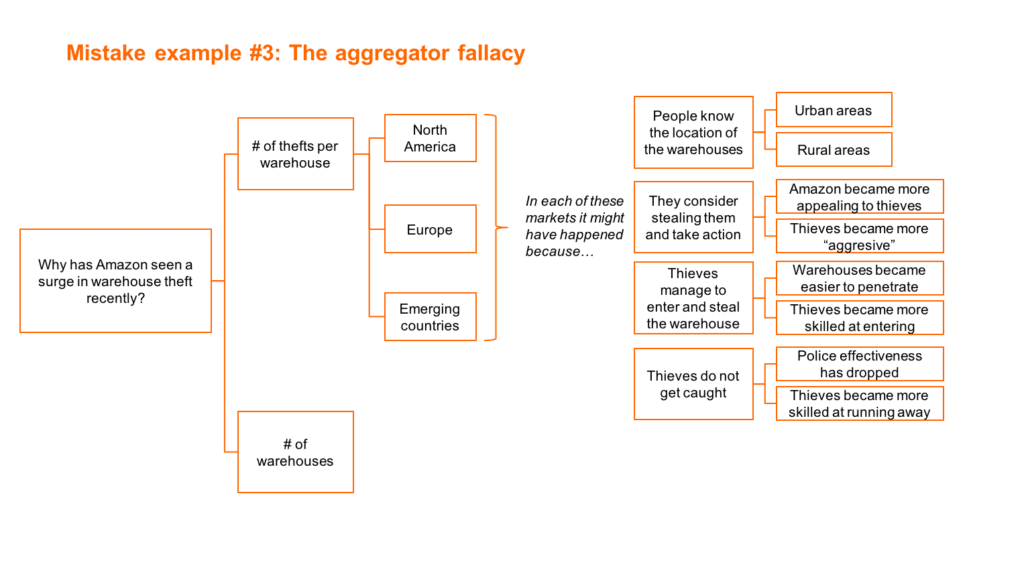

#3 - Guillaume and the "aggregator fallacy"

There are many problems with the Issue Tree below, for instance:

- A regional segmentation early on when that’s not a really relevant factor to explain the problem (as in Mistake #2)

- This regional segmentation isn’t even MECE (there are emerging countries in Europe and he forgot all developed countries in Asia)

- A lack of $ value of theft (again, as in Mistake #2)

- The way he breaks down a process structure to explain a surge in # of thefts per warehouse isn’t very insightful/relevant

But I want to call your attention to one other mistake which is related to causal effects. I call it “the aggregator fallacy”.

Can you spot it?

Let me ask you one thing… If the number of gas stations raise in a city by 2X in a year, will sales of gas increase by 2X as well?

Will they even increase by 10 or 20%?

Not necessarily!

More gas stations don’t drive more demand for fuel (unless there’s very few, high priced gas stations in town, but let’s leave extreme scenarios aside).

Yes, there might be 2X the number of gas stations because demand skyrocketed. But it could also be the case that gas stations were a really profitable business and entrepreneurs entered this market even thought there was no increase in demand.

It could also be the case that some people who don’t know what they’re doing entered the market even though demand didn’t increase and profits weren’t that high (and everyone’s losing money now).

So if you were to find out if demand for gas increased in a town one MECE structure you could use is “# of gas stations * avg. amount of gas sold per station”, but that wouldn’t be the best one.

Why?

Because # of gas stations don’t drive demand – more cars and more usage per car does.

The same thing is happening with Guillaume’s structure.

More warehouses don’t drive more theft. They don’t cause more theft.

Say, for example if Amazon had restructured their operations and they had switched from 10 huge warehouses to 100 smaller ones, with the goal of having faster delivery. Would it be ok for theft to increase 10X? Would it even be ok for it to increase by 50 or 100%?

Probably not, right?

Amazon’s carrying the same number of items, they have roughly the same number of employees (considering internal theft) and if they have their security systems in place, they’re not necessarily more attractive to external burglars (if anything, it’s harder to steal a smaller warehouse than a huge one).

More warehouses shouldn’t cause more thefts. The warehouse is not a driver of stealing just as the gas station is not a driver of demand for gas.

The warehouse and the gas station are merely aggregators of something. The warehouse aggregates products to be shipped (or stolen) and the gas station aggregates fuel to be sold (or not sold in case of a flat demand).

Which is why I call this mistake “the aggregator fallacy” – thinking that because the aggregator has increased that it has caused your problem.

Instead, try to build your Issue Trees with some causal relationship in mind. In the case of the gas station problem, that’d be “# of cars * fuel used per car”.

In the Amazon theft case, you could use “# of products in the warehouse * theft rate” if you assume that more products cause more demand for burglars or “avg. crime rate where Amazon warehouses are located * % of those crimes that are in Amazon’s warehouse” in case you assume that overall crime rate is a given and you can only control your exposure to it.

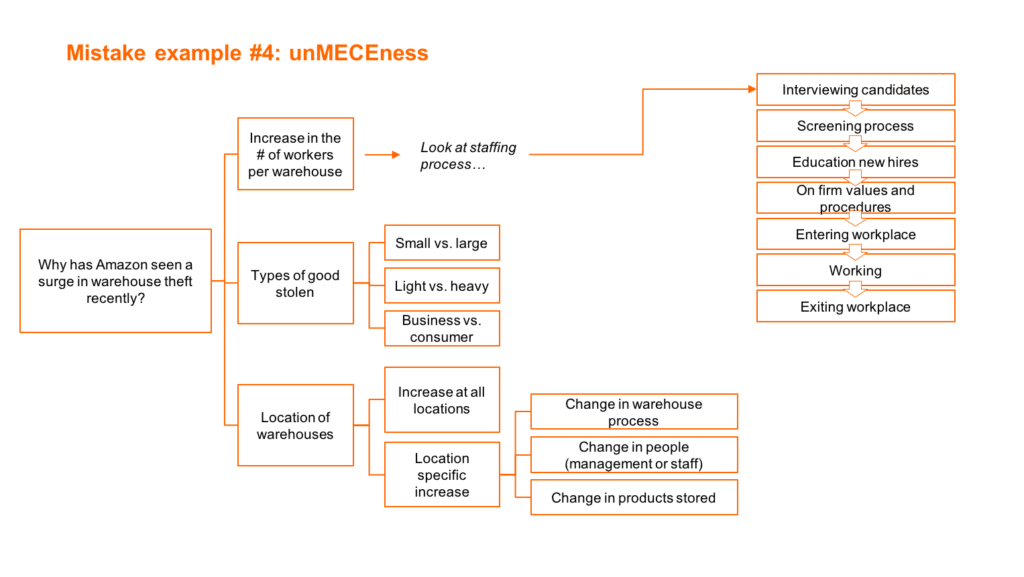

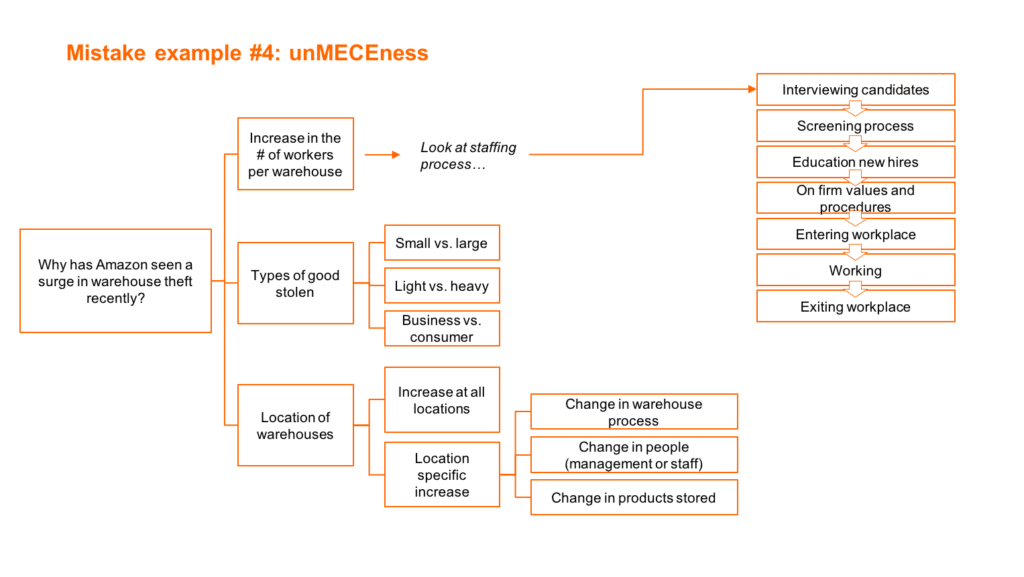

#4 - Jimi, the unMECE

Again many problems with this Tree.

You can mistake-hunt later at your own pace, so I’ll just point out to the ONE FATAL MISTAKE YOU SHOULD NEVER MAKE:

Jimi wasn’t MECE on the first layer of his Issue Tree.

In part because he insisted on using a conceptual framework (the hardest of the 5 Ways to be MECE) without needing to do it (as a theft problem is a numerical problem).

In part because he didn’t know how to create a MECE conceptual framework (as we teach in our courses).

And this would’ve gotten Jimi rejected from a real case interview at McKinsey, BCG, Bain or any other firm.

And it would probably get him fired if he was in charge of Amazon’s warehouses.

Don’t be like Jimi.

Always be MECE (and especially so on the first layer)!

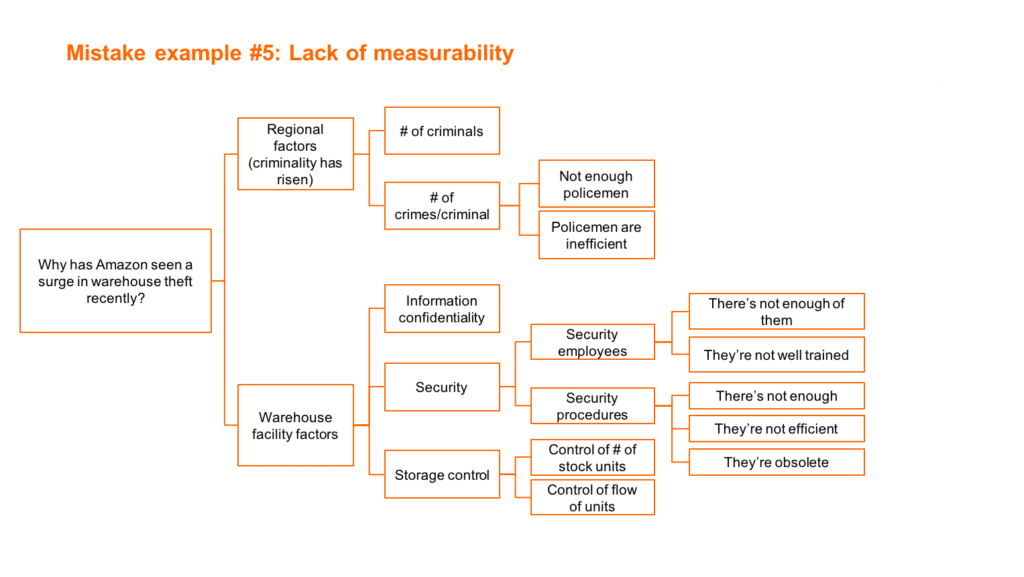

#5 - Was Natalia rejected due to a simple mistake?

I actually like this Issue Tree quite a bit.

It’s well built, although there are a couple of problems.

And it’s interesting because Natalia, the lady who built this tree had been rejected from a Bain and a BCG final round before. She was preparing to try again. That means she was good enough to actually get to the final round but made some mistakes that prevented her to get the offer.

Maybe her mistakes were showing in her Issue Tree?

Perhaps… Let’s take a look:

There are two great mistakes with this tree.

One we’ve talked before – Natalia went for a conceptual structure to break down the “Warehouse facility factors” bucket and had trouble building it. There’s overlap between “Security” and “Information Confidentiality”. Also, there are many things not considered here (including theft caused by internal employees).

But the one mistake I wanna call your attention to is much less obvious. It’s more a nuance than a mistake.

It is on the first layer.

The way she build it is much better than many alternatives: there’s external factors (crime) and internal factors (the warehouse itself).

HOWEVER, it’s really really tough to test which one is causing the surge in theft. These things look measurable but they’re not really.

Why?

Because measuring overall crime is a pain. And getting that data, an even higher pain.

Just to give you an example: what crime data should we consider to prove/disprove the fact that external crime has risen? Should it be overall criminal incidents? Thefts only? Warehouse thefts, specifically?

Also, how regional should the data be? Neighborhood? City? State?

And because you can’t measure “warehouse facility factors”, it’s hard to exclude a whole branch of the tree. Which means this tree is not very “eliminative”, because the factors in the first branch aren’t falsifiable.

Now, I’m being really picky here just to make a critical point to you.

Maybe in a real interview Natalia would’ve been able to come up with a test that would reliably eliminate a whole branch.

And maybe the problem could be solved without that kind of rigorous testing (e.g. maybe they completely switched their security personnel and had security holes in the process, so the cause would be obvious).

But if the situation was harder, more nuanced it would be tough to Natalia to actually diagnose the issue.

And whether she would be able to actually do it in real life is the #1 question in the interviewer’s mind.

Her first layer is not bad, but there are other MECE structures as insightful as this one that would also be more testable, more falsifiable.

And in a final round that could make all the difference.

Commonly Asked Questions

Learning from the mistakes of others is a great way to accelerate your learning curve!

But still, you might have some questions in your head.

Here are some of the questions I have been asked about Issue Trees throughout the years (and the best answers I have to those)…

Issue Trees are one structuring technique but they’re not the only one.

So there are actually two questions within this one: (1) How do I know if I should use a structure to solve the problem and (2) How do I know if I should use an Issue Tree or another technique.

Great questions!

Let’s start with #1…

You should use a structure to solve a problem, well, when you want to solve it in a structured way.

And when’s that?

Well, whenever you want to be able to foresee the steps to the solution of the problem.

That is, when you must have a due date of when the problem’s going to be solved (which is whenever you have a boss or a client, for example) or when you want to distribute the problem for other people to solve it (your employees or an outsourced company, for example).

That means almost always, especially in the professional world, where people have bosses, employees and clients.

Question #2 is a bit trickier to answer…

There are other structuring techniques – ways to break down the problem – that you can use. So, when to use Issue Trees and when to use the others?

Basically there are two scenarios: either you want to split the problem into components of the problem, or you want to look at the problem from different angles/points of view without actually splitting it.

If the first, use an Issue Tree; if the last, use another tool (such as a conceptual framework, as we teach in our free course on case interviews).

How to know which one you want is a bit more complicated and would take an article on its own to explain.

If you want the full details, check out our free course that you can find in our homepage or throughout this article, but here’s the long story short: if you want focus, efficiency and logic onto a well-defined problem use an Issue Tree and if you want awareness and insight onto a messy problem, use a tool like a conceptual framework.

A lot of people who teach case interviews say you should start with a hypothesis.

And they say that because MBB consulting firms (MBB stands for McKinsey, BCG and Bain) work in a hypothesis-driven approach. That means they come up with hypotheses and test them to find the truth (much like in the scientific method).

Being hypothesis-driven is tricky because you also have to be structured and MECE.

So, how do you make your hypotheses MECE?

Well, one way some people figured out is to build a MECE tree and just throw the word hypothesis around. If it were in a case investigating why profits have fallen, this would sound something like this:

“My hypothesis if that profits have fallen because sales are down. To know if that’s true we need to look at sales and costs.”

Notice how there’s ZERO value add to using the word “hypothesis” in the phrase above. If the guy had just asked for sales and cost data he’d ask the same questions, do the same analysis and reach the same conclusion.

If you just want to use the word hypothesis like that, go for it, but there’s absolutely no need to do it. If your buckets are MECE and testable with data, you can just lay out your Issue Tree with no “hypothesis” and test the buckets.

However if you can’t make your structure MECE/testable, you might need to use a hypothesis, but it’s a completely different type hypothesis than the one I’ve shown you above. Instead of being just a random guess with the word hypothesis on it, it must have a structure which we teach in the “Hypothesis Testing” module from our free course.

Great question, glad you asked that!

Clarifying questions are the questions you use to define the problem so you can create your structure / Issue Tree.

You use them to understand the problem better.

If the answer to a question you ask could potentially lead you to solve the problem then the question is a part of the structure of the problem and should be within your Issue Tree.

Drawing Issue Trees on paper is good practice whether you’re in a case interview, helping a client or solving your own problems.

The reason for that is that having it on paper makes it easier to communicate the ideas and frees up space in your mind so you can actually think about each part of the problem.

Not drawing the tree is kind of like memorizing a map – it’s helpful, but the whole purpose of the map is to be there when you need it without you having to know anything by heart.

But drawing does take a bit of time and in answering certain questions in case interviews, interviewers want you to be quick and may even ask you not to use paper. THIS DOES NOT MEAN YOU’RE ALLOWED TO BE UNSTRUCTURED.

It basically means they want to see if you can be structured and communicate your ideas in a structured way even when you don’t have a lot of time to think through a structure and draw it on paper.

Issue trees are a representation of how a consultant thinks. That means consultants think in Issue Trees.

They communicate using these trees as the underlying structure of the ideas they’re thinking through.

So if you don’t have time at all to think, you don’t have to draw your Issue Tree on paper, but you still must communicate as if you were going through one.

This is a super common question, and a highly context dependent one.

If you’re in an interview and it’s a more conversational, back-and-forth style, you should use less layers and get data so you know where to focus on (and dig deeper on that one).

If you’re in a more structured rigid interview format without a lot of back-and-forth, you should use more layers and they may never give you data.

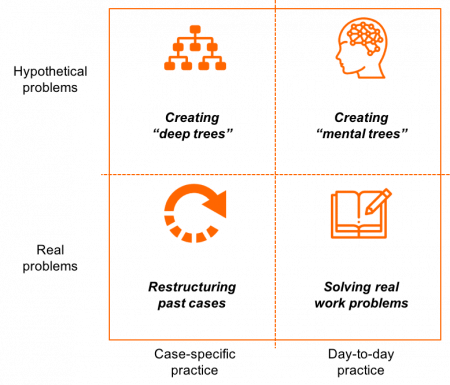

The first scenario will typically happen at BCG and the second at McKinsey. Other firms will depend more on office / interviewer.