(This article is part 4 of the series “The 5 ways to be MECE”, to go back to part 3, click here. To go back to part 1, click here)

When I started preparing for case interviews I had a lot of difficulties learning how to structure. I troubled me when people told me “you know, you just have to break down the problem into its component parts”. Yeah, right. If it were that easy, everyone could do it. And then everyone would get offers. Or maybe there wouldn’t be management consultants around. I don’t know.

People who tell you structuring “is just breaking problems down into its components” should have no business teaching others how to do it. You know that friend of yours who’s an incredibly talented musician, and when you go after him to get a tip or two they say “you just have to feel the vibes and go along with it”? Yeah, terrible teacher.

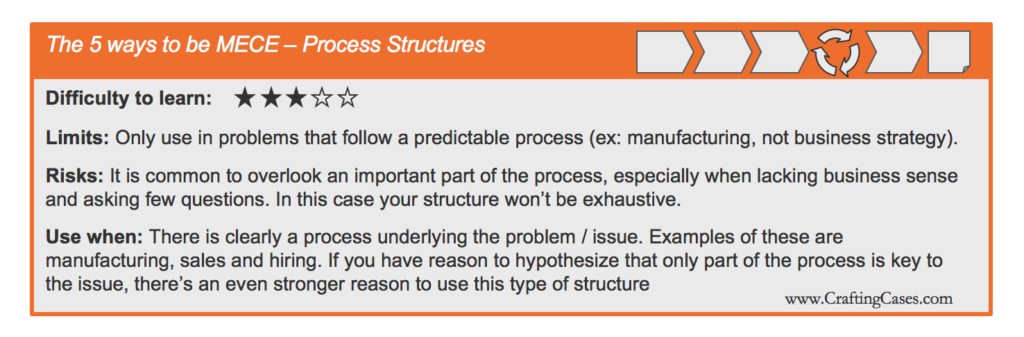

But there’s a situation where that advice applies. There’s one way you can structure a problem that is indeed just breaking it down into the parts. I call these structures “Process structures”.

A lot of the problems management consultants solve are related to processes. In fact, you can think of anything big businesses and governments repeatedly do as a process: manufacturing, logistics, maintenance, sales, hiring… The list goes on.

The great thing about processes is that they have a beginning, some steps in the middle and then an end. Breaking down any problem that has an underlying process into its steps is a sure way to be MECE. You can’t miss a thing because you’re covering the whole process and everything happens within that contained reality.

For example, imagine you need to find reasons why the manufacturing cost of a widget has increased. You can break this problem down to each manufacturing step, check if the cost has gone up in that step and if so, examine why. If manufacturing cost as a whole has gone up, at least one step’s cost must have gone up as well. Same if you need to find ways to increase sales efficiency: just break down the sales process into its steps and find ways to increase efficiency in each step. Or even eliminate a whole, useless step.

The only risk you run is to miss a part of the process, which is something you can check with interviewers by showing them how you think the process is like and validating if it really happens that way. This is exactly what you do with clients in a real project, so it’s safe and sound.

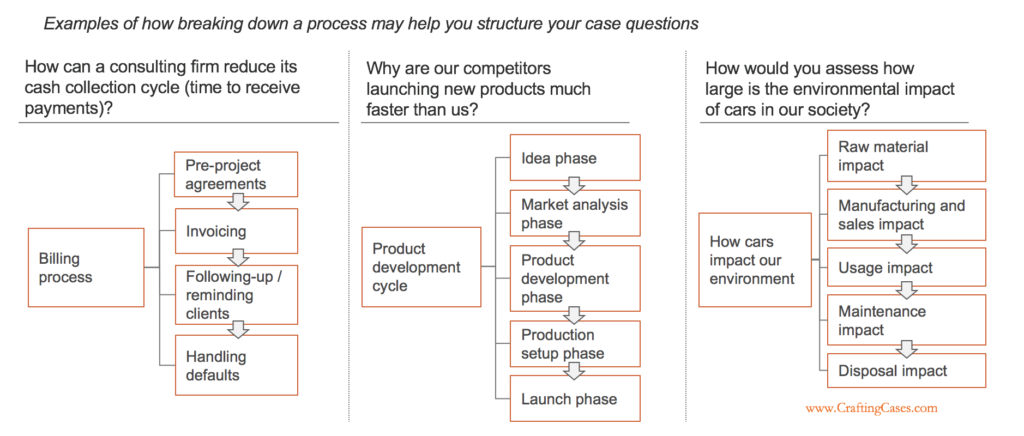

Here are a few examples of how you can break down the problem’s underlying process to have a clear, MECE structure to solve different problems:

Notice how breaking down the process forces you to think “outside of the box” and be thorough. Most candidates who aren’t systematic in the “cash collection cycle” case miss ideas from one or two steps (this varies by candidate). On the “product development” case, having a clear process structure helps us quickly know in which phase are our clients faster, saving a lot of guesswork coming from random hypotheses. The third case, in my opinion, is the one that shows the full power of this type of structure: the vast majority of candidates who aren’t proficient in using process structures forget all of the parts of the lifecycle of a car but the usage. They miss four different steps that have significant environmental impact. These are people who’ll have a hard time getting an offer.

Some things are not usually thought of as a process but can if you just stretch the mind a little bit.

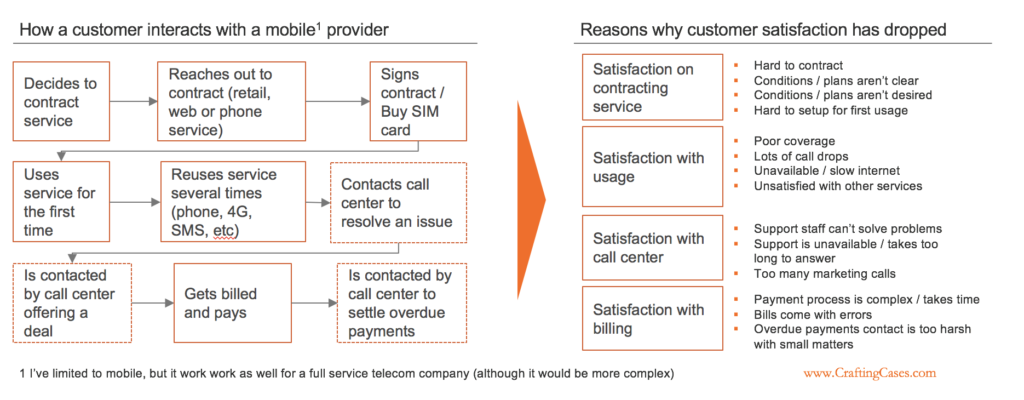

Take one example: telecom customer satisfaction. Because telcos are a business based on recurrence, they’re usually concerned about customer satisfaction levels (I know, many times it doesn’t seem so…). Now, most folks wouldn’t think of customer satisfaction as a process, and the reason is that it’s not a real process. It is also a hard variable to break down during a case. So, imagine your interviewer had asked you possible reasons why a telco’s customer satisfaction levels have dropped. How would you give a MECE answer to that problem?

Well, let’s do a bit of mind stretching. A telco customer changes its satisfaction levels with each interaction. People get mad at telcos when they’re dealing with them somehow: dropped calls, poor internet signal, poor customer service and so on. Luckily for us, telco customers interact with them following a certain (irregular) pattern. In other words, a process. Here’s how a typical customer might interact with a mobile provider, and how we could structure this case based on that:

In a real interview, you can think the process on the left out loud before you create your MECE structure (such as the one on the right). You could even use the raw steps laid out on the left as your structure.

I often tell people to do just that, to stop and think out loud about the problem. Their concern is always the same: “won’t I take too much time to do this?”. Absolutely not.

Here’s a rough statistic: every single candidate I’ve applied this case on has given me hypotheses regarding usage. 80-90% of them regarding the call center. 20-30% regarding contracting the service. No candidate has ever included billing in their structure. Guess where the answer to this case lies? That’s right. This telco has a billing issue that is causing massive dissatisfaction among customers, who are being charged the wrong amount.

Interviewers LOVE the candidate who takes the time to come up with the right structure because this will be the consultant that solves the client’s problem the fastest. You’ve all heard that phrase: “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe”, right? Well, as a consultant, your axe to chop down a problem is the structure you use. Well worth it spending a couple of extra minutes to get it right. Your interviewer will be glad that you did when you nail the case afterwards.

. . .

When coupled with these mind-stretching skills, process-driven structures are highly flexible: they work with almost any operational (i.e., day-to-day) issues companies and governments face.

As in the Algebraic structures, you will cause a better impression on your interviewer if you include qualitative issues after each MECE element of your structure – this shows insight along with the logical thinking, and both are valued.

But some problems aren’t numerical problems nor processes. Even if you practice mind-stretching, you can’t really find an underlying process to it.

Or maybe it’s a long-term problem, and the qualitative issues and interrelationships between the parts are more important than the parts themselves. What do you do, then?

Then it’s time to use the third core structuring technique. A technique so powerful you can arguably solve any case through it, but difficult enough to take more time to learn than all others combined.

Conceptual frameworks are their name, and it’s much more than memorizing the 3Cs and the 4Ps: it’s about creating your own from scratch. Wanna learn how? The next part of this article series will teach you that.