(This article is part 6 of the series “The 5 ways to be MECE”, to go back to part 5, click here. To go back to part 1, click here)

Almost every great structure has a lot of nuance to it. One way to add nuance is to embed a few relevant segmentations within it.

Segmentations are mostly overused as a way to structure a problem in part because they’re easy to learn, in part because they’re easy to teach. Most case interview resources out there show you how to be MECE using segmentations as examples. That’s lazy. It is lazy because while they’re good at adding nuance, they aren’t often strong enough to solve a problem on their own. I am not going to be lazy, and neither should you.

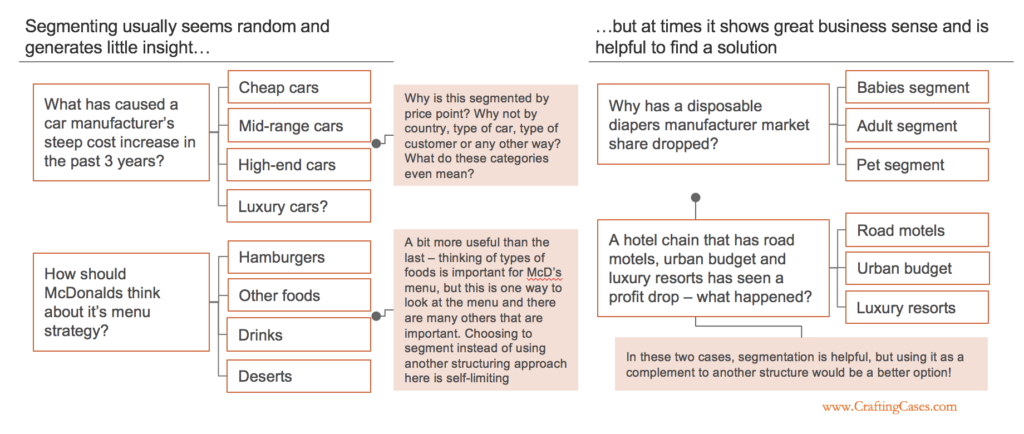

Segmenting is essentially cutting a slice of the problem. For instance, you could segment a company’s customers by age group (0-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61+), by gender (male, female), by country, etc. Another example: you could segment a company’s revenues by product line, by country, by type of customer, by month, etc. Notice how segmenting is different than finding the mathematical drivers (the essence of the Algebraic structures) in that you have a clear criterion to slice the data here.

The problem with using segments is that while MECE, you structure will only generate insight if you have chosen the right segmentation criterion. There are dozens of ways to segment almost any problem and if you don’t pick the right one, you will waste your time instead getting closer to the answer. What candidates tend to do in this case is to try another segmentation pattern. Do this enough times and your interviewer will grow bored with the impression you’re guessing with no systematic approach. You’ll get mentally rejected soon enough.

There are situations in which you might wanna use segmentations to create your structure, however.

One is when the case gives you clear indications that the key of the case lies in one specific segmentation pattern. This can be due to industry specifics, such as in the Diaper example above or due to information on the case question or throughout the case, such as in the Hotel Chain example.

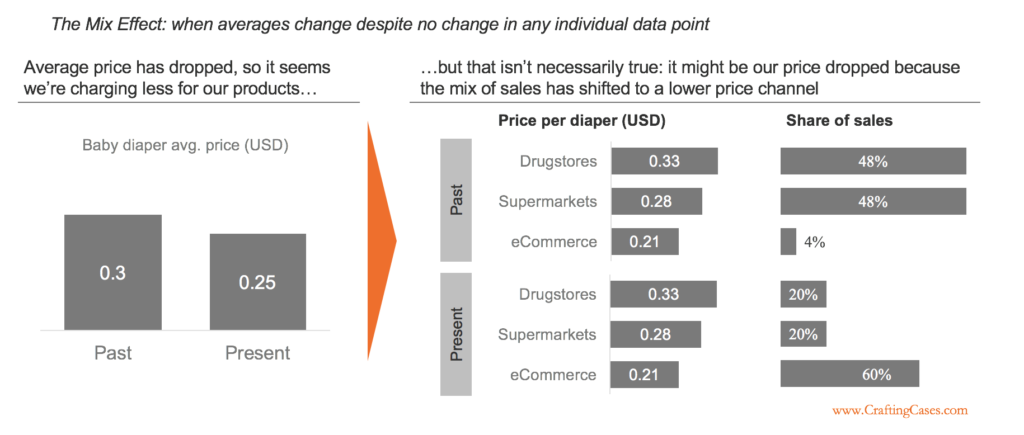

A second situation where you might want to use segmentations is when you’re suspecting there might be “mix effects” skewing the averages around. A “mix effect” is an effect that comes up often in case interviews, in which the average performance changes not because underlying performance has changed, but because performance is different across segments and the weights of the segments have varied throughout time.

For example, a company’s average price for a product may have dropped despite no change in pricing policy. Instead, customers might have started shopping in channels where the company offers a lower price point.

In the example above, a diapers company has seen its average price drop from 30 cents per diaper to 25 cents per diaper. One might think prices actually dropped to customers, and that someone in the company or on the retailers has changed the price. In reality, nothing changed but the mix: customers started buying online and diapers in this market are, and always have been cheaper when bought online. This change in mix of distribution channel was the only cause behind the price drop.

Although the change in mix is an excellent hypothesis on this case, the segmentation criterion that would reveal that is far from obvious. Instead of distribution channel, it could be that customers are moving from packages with few diapers to bulk packages, which have a better price per diaper. It could be that the company is growing larger in less developed countries and that they charge less in those countries. How can you know which one is the right segmentation criterion? You can’t. You have to guess and hope to be right.

If you suspect there are “mix effects” in the case you’re solving, by all means segment the data to check that out. From our observation of real case interviews our clients have solved with management consulting firms, just over half of all case interviews have “mix effects” as an important element to find the solution, so make sure to keep it on your radar. Short term performance changes, many which happen in profitability cases are especially prone to this.

But even then, it is best to use segmentations as a complement for another structure type.

If you rely too much on segmentations as a way to break down your problem, you will soon have an impatient interviewer thinking you’re guessing too much. The interviewer’s feeling should be that you’re using a structured, systematic approach to solve your problem. Anything short of that will get them impatient, and segmentations are a less systematic approach than others.

The best situation, then, to use this type of structure is as a complement to another, more insightful type of structure. Segmentations are excellent complements, even though they rarely generate enough insight to solve the case on their own. Think of them as spices and herbs in cooking. A dish made of only spices and herbs is not really a dish. But take a simple dish and add a few well-chosen spices, and you have a delicious meal!

Using segmentations this way is enough to cover all situations where you must use segmentations, that is, industry-specific situations, case-specific ones as well as “mix effects”. It is also safe to use segmentations as a complement whenever you feel you’d get useful nuance in a case. Used in addition to other types of structures, there’s no problem if your guess on the criterion / pattern isn’t right. You’re testing hypotheses, and it’s okay if a hypothesis is wrong as long as you have a backup plan in your main structure.

. . .

Adding a couple of segmentations here or there in your core structure is an excellent way to add some spice to your problem-solving approach. But you can’t do this too much, no one likes an over spiced dish.

What to do, then, when you want more structure? Or when you can’t find a structure for a specific question?

There’s a way to instantly generate a structure to answer any question, case interview or not. You can use this technique to create structure where you can’t find one or to add a lot more logic to the way you speak. That’s the power of Opposite words. I’m gonna teach you this in the next part of this series.

But remember, with great powers come great responsibility!