(This article is part 8 of the series “The 5 ways to be MECE”, to go back to part 7, click here. To go back to part 1, click here)

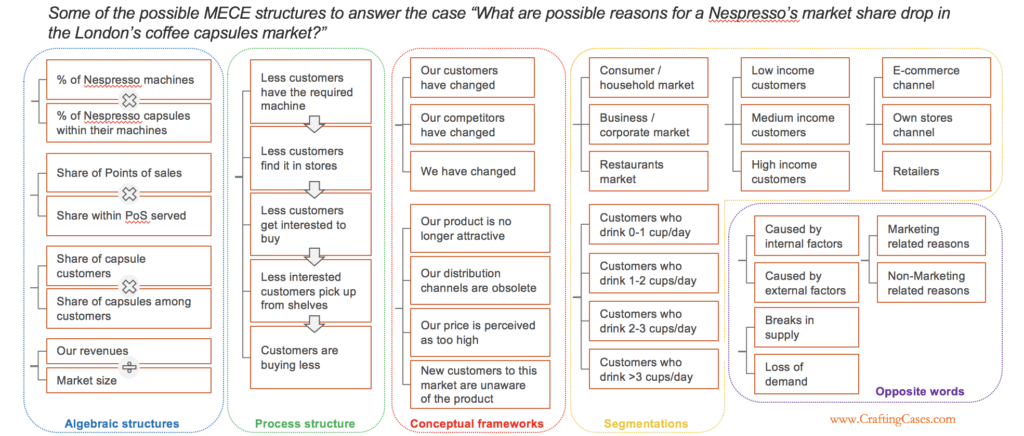

Remember this chart from Part 2 of this series?

It showed you if you learn the 5 techniques to be MECE you’ll never run out of structures again. That you can find several MECE structures to any question your interviewer raises to you.

And as we’ve seen in Part 1, being MECE is wonderful, because it enables you to do several remarkable things on interview day:

- To know how to start any case, no matter how uncommon, with a structure that is sure to solve the problem

- To show strong confidence on interview day

- To effortlessly connect with your interviewer during the short time you have together

So far we’ve covered each of the 5 techniques, and you know what each one is for, what their strengths are and common risks and pitfalls. If you learn this well, you’re ahead of 9 out of 10 candidates. You will never get stuck again.

But if you invest just a bit more effort you will learn a superpower.

If you learn to tie-up these five techniques in a coherent way, you will learn to create issue trees from scratch.

[Update: I’ve recently written The Definitive Guide to Issue Trees, which is a comprehensive guide to learn and practice how to create issue trees.

I’ll be honest with you: when I was preparing for case interviews, I didn’t care a whole lot about issue trees. For me, it was just a name they gave to these weird diagrams that, even though they divided the problem neatly, were hard to make and didn’t seem valuable.

Oh, was I mistaken!

Issue trees are not only easy to build; they’re golden!

They’re a blueprint of how the minds of MBB consultants work. Sometimes consultants will use it explicitly, but often it’s implicit, in the back of their heads. I could get any conversation between two people from McKinsey, BCG or Bain and draw out the issue tree that’s implicit in their conversation.

In fact, this is how many people took notes of meetings within McKinsey.

Draw out an issue tree specific to the case your interviewer gives you and you’ve caught their attention. Now they know you think as they do.

Thankfully, issue trees are super easy to build once you know the 5 ways to be MECE. Learn this and you will have an incredible advantage over other candidates, those who come to interview day using the same frameworks they’ve used in every single practice occasion. While they can’t draw issue trees because they haven’t mastered the 5 techniques, you’ll be speaking your interviewers’ language and showing them you think as they do.

Here’s how you build an issue tree.

First, you break down a problem into a MECE structure like the ones in the chart above. You can use any MECE breakdown, but some are better than others (we’ve discussed principles, pros and cons of each technique in the articles related to each). This is your issue tree’s first layer.

To build the second layer, you pick each part of your 1-layer structure and break it down again. You can do this using the same technique or a different one than the first level. For example, if on the first layer you broke it down using an Algebraic structure, you can do the second layer using Conceptual structures. You can even use different techniques in different parts of the same layer. There are no hard rules as long as you keep each breakdown MECE.

Rinse and repeat until you have as many layers as you need.

Once you’ve broken down the problem enough times, you’ll have a custom, MECE structure for the specific problem you’re solving. Welcome to the elite club of those candidates who build their own structures.

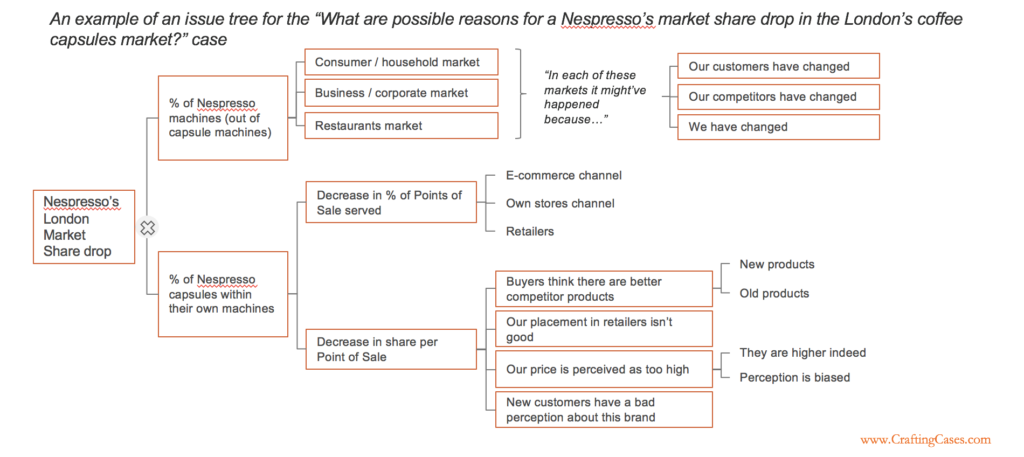

Here’s an example of an issue tree for the Nespresso Market Share case that was built using the very approach I just described.

Is this the best structure ever for this case? Not really. Does it show the interviewer you can think in a structured way about this unique problem and that you’re not using memorized frameworks? Certainly!

I have never seen a candidate who gets double offers who can’t do this. Most candidates who get one offer are proficient. If you’re not willing to count on luck, please do yourself a favor and learn this. I swear it isn’t hard after a few tries.

Really, just try it!

The “science” part is pretty straightforward: to break each layer down using a MECE structure that is rooted at one of the 5 ways to be MECE. But not all MECE structures are created equal. Some are better than others. This is the “art” part of the skill.

Let me show you some nuances of the issue tree above. Later I’m going to show you a tree that isn’t very good despite being as MECE as the one above.

First, let’s look at the positives

The first positive is that the first breakdown uses the algebraic technique in an elegant way. This is highly useful because (i) it leads to some insight (that the market share problem could be caused by a problem in selling devices as well as capsules) and (ii) it is quantifiable. Because it is quantifiable, the interviewer knows with just a little bit of data you could pinpoint the source of the problem and ignore the other half of the problem. This saves a lot of time and is a smart way to work. Had you started with a conceptual structure, you’d have a hard time quantifying the case in a way that allows you to minimize the amount of work needed by eliminating whole parts of the problem.

Another interesting (and positive) aspect of this structure is the double structure within machine share: I segment by market to quantify, but let the interviewer know I will use a conceptual (3Cs) structure to analyze why there was a share drop in any segment that’s performing poorly. I’ve chosen the 3Cs because these segments have different demands and competition. Even our own operations must be a little different. I used one technique to quantify and another one to reach insight. Since I couldn’t find one breakdown that was good for both, this was the next best option.

A third cool feature of this structure is that it uses 4 of the 5 techniques. The core techniques tend to be to the left (on the upper layers, because they tend to be more insightful). But I also use “segmentations” and “opposite words” to make the issues more granular to the right side of the tree, where problems are more specific. More techniques in a single tree don’t necessarily mean it’s a better tree, but if you’re thoughtful on how you choose the breakdowns, you’ll tend to get a better result.

If I were an interviewer, I’d be pretty satisfied with a candidate who showed me a structure like this one.

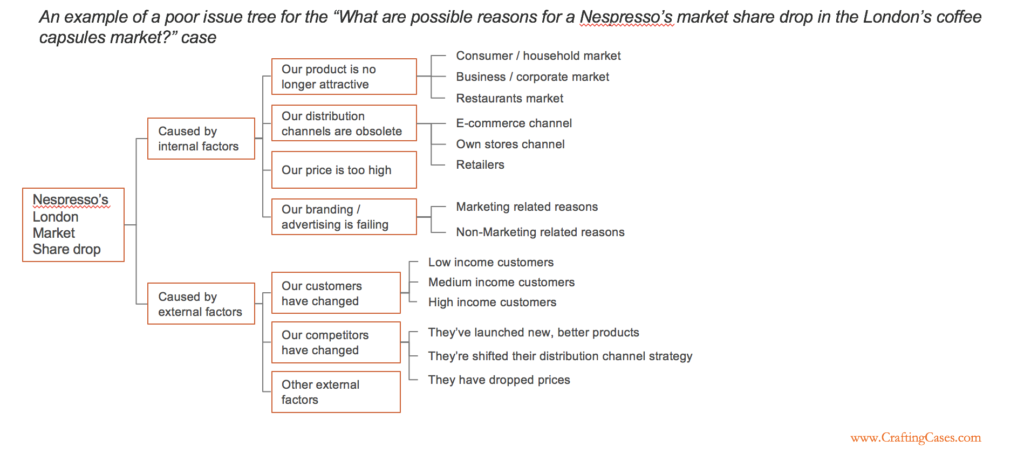

Now here’s an example of a MECE issue tree for the same problem that isn’t built with enough skill. It almost feels it was put together mindlessly, as if actually solving the problem wasn’t a concern in the candidate’s mind.

This structure is as MECE as the last one! But it’s not as good… For three main reasons.

First, the initial breakdown brings neither the ability to focus nor insight on the nature of the problem. On the last structure, the first breakdown was not only quantifiable (which helps you focus), but also insightful (it showed market share depended on share of machines AND share of capsules, two completely different things). This one is neither. Internal vs. External can be used to almost any problem, and thus it isn’t the best option to any.

The second issue with this structure are the random segmentations. Why dividing product attractiveness by business segment? Do customers change the type of product they prefer is they consume at home vs. in the office vs. in a restaurant? Perhaps, but not likely. Is there any evidence or logic behind segmenting a change in consumer’s preferences or behaviour by income level? I don’t know, it seems to me age or other factors could be equally important. The pattern you choose to segment your structure with should lead to an insightful hypothesis, otherwise it is just random (which will give you random chances of doing well in your cases).

The third issue with this structure is the reuse of the 4Ps – it is used to break down “Internal factors”, and a modified version is used to break down “Competitors have changed”. While this isn’t as critical as the last two reasons, it shows the candidate could’ve reorganized the structure better to avoid redundancy. The 4Ps could be only mentioned once if it were being used to compare Nespresso’s marketing against its competitors (that is, working with them in comparison, not studying each in isolation).

These three shortcomings are aspects of underlying reasons that make the first structure good and the second structure poor. MECE is the first principle of structuring, but there are others that are important as well. It’s a lot like driving: good drivers put safety first (that’s the first principle), but great drivers are also fast, economical, aware of other drivers (these are some of the other principles). While both structures are MECE, the first is more insightful and efficient in solving the problem.

So, to create issue trees from scratch, you need to combine the 5 techniques to be MECE in breaking down the problem. MECE is only the beginning, however. You’re aiming to be insightful as well.

Notice most breakdowns in both structures were already present in the first chart of this article, where I got back the 13 MECE structures to the original problem from Part 2 of this series. You need to combine the five techniques skillfully. Otherwise, your structure will be MECE, but poor.

Mastery of structuring issue trees is having both the science AND the art.

But why would you want to learn to structure issue trees again?

As I’ve said, issue trees are representations of the inner workings of the mind of a top consultant. Not only are they the easiest way to structure a case from scratch, but they’re also the foundation of the other two methods we teach candidates to structure from scratch: context-driven structures and objective-driven structures. Each method has its advantages and is better for certain situations, but issue trees are the fundamental technique. They’re the backbone of the reasoning, whether you use them explicitly or not.

Before you move on to the last part of this series…

An inch of action is worth more than a mile of intention, so before you move on, I have a small challenge for you.

Recall the last case you’ve practiced with someone and try to come up with a MECE issue tree created from scratch that would fit that case perfectly. Try to apply all the principles and techniques that we’ve gone through in this series and this will help you internalize them.

Grab a cup of coffee (or tea) and a piece of paper and do it.

I’ll be waiting for you in Part 9.

. . .

Now that you’ve learned the 5 ways to be MECE, is it time to leave?

No no.

In the last part of this series, I’ll show you a synthesis of what you’ve learned here (in a neat way that lets you “get it”) and what are the next steps on your journey to master structuring and solving case interviews.

I know you’re short on time, so I made it count.

Take me to Part 9 of “5 ways to be MECE”.

Or check out The Definitive Guide to Issue Trees